This article was published in The Kyiv Independent media outlet

Editor’s Note: This story was sponsored by the Ukrainian think-tank Center for Democracy and Rule of Law (CEDEM).

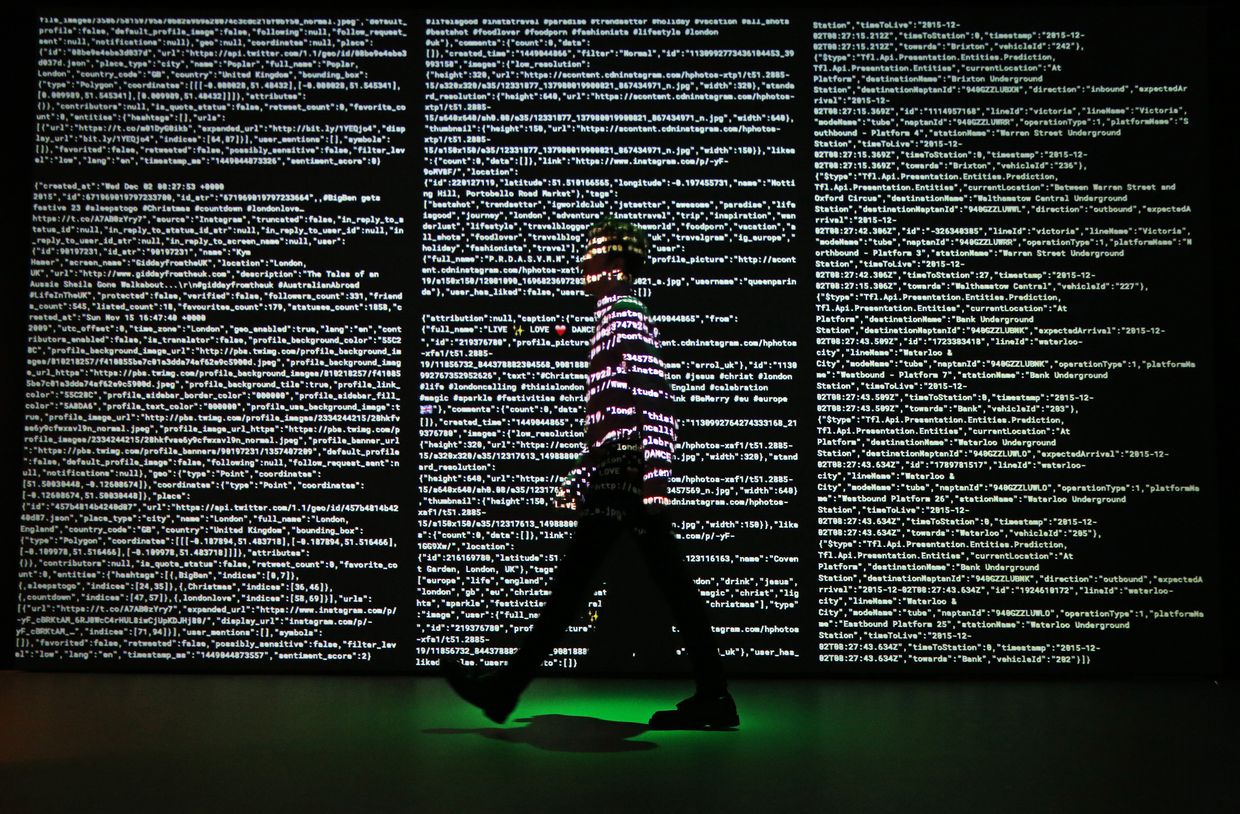

As Russian missiles pounded cities across Ukraine on Feb. 24, 2022, Russia waged an information war against countries around the world, primarily through social media. The goals of Russia’s infowar were to confuse the public, promote false narratives, and weaken support for Ukraine.

The onslaught of Russian disinformation continues to this day. On Jan. 26, 2024, German authorities exposed a vast network on social media platform X (Twitter) aimed at turning Germans against support for Ukraine.

In the context of Russia’s war in Ukraine, social media’s moderation policies can be a matter of life and death, but platforms have struggled to find the right balance when moderating content. Experts criticize companies such as Meta – the company behind Facebook and Instagram – for blocking harmless content while letting malicious lies flourish.

“The reality is that platforms are actors in today’s armed conflicts,” says Chantal Joris, legal officer at Article 19, a leading freedom of speech nonprofit. “Now, they need to live up to their responsibilities.”

First challenges

Social media started in the Wild West of Silicon Valley. According to Eric Heinze, a professor of law at Queen Mary University London who specializes in freedom of expression, this meant that early platforms had an expansive, First Amendment approach to speech – almost everything was permitted.

In the mid-2010s, platforms faced unprecedented challenges: ISIS used platforms to recruit and spread propaganda; Russia used them to meddle in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. By 2020, Meta’s policies were more restrictive than legally required – cracking down on COVID-19 fakes and other conspiracy theories.

Finally, governments around the world, as well as the European Union, took notice. The EU’s gargantuan Digital Services Act (DSA) comes into force in February this year, imposing extensive legal obligations on social media giants.

Content policies from 10 years ago are unrecognizable today. While platforms like Facebook are restricting more content than ever, disinformation is proving difficult to uproot, says Heinze.

Black box

Meta’s “Transparency Center” outlines its policies on prohibited speech on its platforms, from incitement to violence, bullying, and hate speech. Each policy comes with a list of examples intended to guide users.

According to Joan Barata, an expert on content moderation and fellow at Stanford’s Cyber Policy Center, the policies still leave much to be desired. He says Meta’s definition of “hate speech” is so vague that it could never be legally enforced.

Moreover, the actual moderation process remains a guarded secret. Meta’s internal criteria, used by AI and human moderators to decide when to ban and block, were leaked in 2017, sparking controversy and debate. Six years later, and following massive policy changes, experts and users alike are left to speculate on what’s going on behind the scenes.

According to Barata, Meta claims to keep the mechanics of moderation a secret due to a fear that bad actors will use the knowledge to circumvent the rules. He says that the real reason is to cover up inconsistencies and subjective decisions, which are an inevitable part of moderating millions of posts per day.

Article 19’s Joris agrees that Meta’s reasoning is flawed. If the rules were precise and consistent, they would have no reason to keep them from the public, she says. Those who want to break the rules do so anyway, she says, by using well-known tricks that evade automatic moderators – like replacing letters with symbols.

Matters of life and death

Disinformation is a powerful weapon that can have devastating consequences during an armed conflict. Equally, access to verified, accurate information is often severely limited during war, and social media becomes a key source. This makes platforms’ task of finding a balanced approach especially difficult.

Joris said that social media coverage of conflict inevitably poses moderation challenges. For instance, while violent content is generally banned, it forms a core part of wartime reporting. Meta initially blocked content covering the massacre perpetrated by Russian forces in Bucha in 2022 but later reversed the decision.

Igor Rozkladaj, deputy director and social media expert at Ukraine’s Center for Democracy and Rule of Law (CEDEM), works closely with Meta’s representatives in Ukraine, helping users appeal bans and shape broader policy.

According to Rozkladaj, Meta’s strict community standards sometimes produce counterproductive effects. One of the challenges is the policy on offensive speech – from angry posts in the heat of the moment to satirical content and memes about Russian President Vladimir Putin’s death – can be a violation.

In March 2022, Meta recognized that in the context of Russia’s invasion, their standard policies would result in “removing content from ordinary Ukrainians expressing their resistance and fury at the invading military forces.” The platform changed its policy, allowing for calls for violence against invading troops.

According to Rozkladaj, Ukrainians are not asking for Facebook to give them free rein to abuse Russians on the internet. What they want is a clear policy that is fairly applied and lets users combat Russian narratives and not wake up to unexpected blocks or suspensions.

In his work appealing bans, Rozkladaj had a 60% success rate in the first year of the full-scale invasion. This is far from good news – it means that more than half of the measures were incorrectly imposed in the first place.

In the context of all-out war, lives could be lost even if a ban only lasts a day. Rozkladaj worked with Ukrainian volunteers whose accounts were blocked for purported violations of community standards. This could impede them from delivering life-saving aid, as volunteers use social media to communicate with those in need, says Rozkladaj.

Experts highlighted that more consultation with regional actors by platforms is necessary in all modern conflicts. For instance, Joris pointed to a recent report by Human Rights Watch, suggesting that any content related to Palestine was disproportionately moderated by Meta in the context of the Israel-Hamas war. Barata cited the ongoing conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo as a “forgotten war” where there is limited engagement by platforms with local actors.

Joris and Barata said that harsh or unexplained penalties against users pose the greatest threat to free expression online. Bans cause a so-called “chilling effect” on speech but often fail to tackle disinformation driven by networks of disposable bot accounts.

CEDEM’s Rozkladaj worked with Liga, one of Ukraine’s largest media platforms by social media following, after their Facebook account was suspended for four months after they posted a satirical piece about the now-dead Wagner Group head Yevgeny Prigozhin.

One of Ukraine’s largest media organizations, Hromadske, had news content on Facebook labeled as “sexual” by mistake, resulting in a temporary ban, suffering a significant loss in website traffic before an appeal restored their page.

Ukraine’s Media Development Foundation studied 57 media organizations and found that 27 had faced social media restrictions since the start of the full-scale invasion.

False positives and mistakes are inevitable, as Meta admits. However, bans on Ukrainian media organizations defending against Russia’s information war can have a longstanding impact, regardless of how long they are.

Ukrainian users on X (Twitter) and Meta-owned Instagram have also complained of “shadow bans,” where a platform limits engagement with a user’s content by tweaking the platform’s algorithm.

According to Joris, shadow bans are far from a conspiracy theory but rather a common tool used by social media platforms to influence what users see.

Shadow bans are particularly problematic because users are not notified, says Joris. They are punished without knowing that they did anything wrong and have no opportunity to appeal.

In its report on social media in wartime Ukraine, CEDEM recommends a whitelist system that gives media organizations additional protections in conflict settings, which would go a long way to fighting back against disinformation.

The future of information warfare

All experts agreed that a vibrant, flourishing media environment is a more effective weapon against disinformation than a heavy-handed blocking policy. The biggest change to information warfare will come with implementing the EU’s flagship DSA.

The DSA will push platforms to be more transparent, which experts agreed is an important step in the right direction. Joris and Barata both praised the DSA for putting a human rights approach at the center of the regulations and emphasizing that enforcement must always be rights-driven.

The legislation includes a “Crisis Response Mechanism,” added after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Joris welcomed the EU’s recognition that crises like armed conflict pose unique risks for speech on social media but said the “state of emergency” approach gives overly broad powers to regulators.

Since the start of the full-scale invasion, Ukrainian users have been at the forefront of debunking Russian narratives and exposing disinformation. Rozkladaj was firm in the belief that a victory against disinformation means giving these users more freedom wherever possible.

Ultimately, there is no certainty about how the DSA will be implemented. As violent conflicts range around the world, social media platforms continue to struggle with finding the right balance in moderating content and face constant criticism for their failures.

Platforms can learn from the war in Ukraine, which shows that engagement with local civil society is the first step towards finding this balance.

Daniil Ukhorskiy

Investigative Reporter

Daniil Ukhorskiy, has been a freelance investigative reporter at the Kyiv Independent since November 2023. He used to work with us full-time between August and October same year. He is an international lawyer with experience documenting human rights abuses worldwide. Previously, he worked for the Clooney Foundation for Justice investigating war crimes committed by Russian forces in Ukraine. He holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in law from the University of Oxford.