Oleksandr Monastyrskyi

Analyst in the field of countering disinformation and improving media literacy,

“Independent Media” program, o.monastyrskyi@cedem.org.ua

Social networks have become an integral part of our daily lives. They allow us not only to read the latest news and communicate with loved ones, but also to become opinion leaders for those who read our posts or comments. However, social networks also have a “dark side”, as they often serve as fertile ground for disinformation.

Although more and more people are learning about media literacy and its importance, disinformation continues to spread rapidly among users. Partly, social networks themselves contribute to the spread of false information, as they instill certain online behavior habits.

It can be assumed that the main factor is the spread of content itself. Some studies show that false news spreads on social networks up to 10 times faster than true news – and it’s not so much bots as ordinary users who fuel the spread of disinformation.

A research group from the Marshall School of Business and the College of Letters, Arts, and Sciences at the University of Dornsife found that posting, sharing, and interacting with others on social networks can become a habit. Their study revealed that among the sample of experiment participants, 15% of active information spreaders were responsible for spreading 30% to 40% of false content.

This presents a certain paradox, as despite the rise in digital and information literacy, disinformation continues to spread actively.

However, the most important question is: why do we still believe it?

To jump ahead, this is a very complex question that requires a separate discussion and a deep understanding of human psychology. Nevertheless, in this consultation, the author aims to highlight the reasons behind our tendency to believe in false news, as this phenomenon has been repeatedly observed in social networks and media.

The goal of this consultation is to examine the psychological aspects and reasons behind how and why people so easily believe in disinformation, despite all the knowledge and skills related to media literacy. The author also seeks to encourage the reader to reflect on the topic of perception and the spread of disinformation. The consultation emphasizes the need to consume information cautiously, consciously, and moderately.

Reason #1: Identity Issues

In an article by The New York Times (link to the original study here), the author outlines the research on this topic and highlights vulnerable identity and the search for like-minded individuals as key factors in why we believe in disinformation, even when we sometimes realize it might be false.

“First and perhaps most importantly, it’s when societal conditions make people feel a greater need for what sociologists call in grouping – the belief that their social identity is a source of strength and advantage, and that other groups can be blamed for their problems”.

In other words, we need security, especially in times of crises and dangers, and we find it in thoughts and views that are approved by the majority. This provides us with a sense of comfort and conformity. This, in turn, leads us to consume information (whether true or not) that allows us to see the world as a constant process of confrontation between our group, whose views are seen as the only correct ones, and an antagonistic group or opponents who are willing to destroy us for our beliefs and are constantly trying to deceive us.

Thus, societies where the basic need for security is not fully met become more vulnerable to disinformation. It is also worth noting that often vulnerable populations, such as ethnic, religious, and other communities that lack the power and resources to physically or informationally protect themselves, are more likely to trust rumors, conspiracy theories, and the like. They often learn this information from members of their own community or from those in similar circumstances – such individuals intuitively inspire trust in them.

Reason #2: The More Disinformation, the Worse It Gets

Studies on why people continue to believe in and spread disinformation reveal an interesting phenomenon – the more often a person encounters the same claim, the more likely they are to believe it. Among scientists, this phenomenon is known as the “Illusory Truth Effect.” Researchers of this phenomenon conducted the following experiment:

“500 people were asked to assess headlines based on their credibility, including headlines from real articles posted on Facebook during the 2016 U.S. presidential elections. They [the researchers] showed participants different headlines over several sessions and invited them to return a few weeks later to repeat the experiment. Participants rated the credibility of fake news headlines they had already seen higher than those they had just seen. Participants gave even higher credibility ratings to headlines they had already seen when they were shown these statements again a week later”.

It is clear that the proliferation of disinformation in the information environment, as well as the frequency of repetition of this information, directly influences a person’s belief in false claims. This is how well-known “bot farms” operate. They try to create a crowd effect, convincing people that many others share a particular opinion. In addition, they mass-distribute and repeatedly share the necessary information so that more people see it over and over again, until they start believing in the desired narratives.

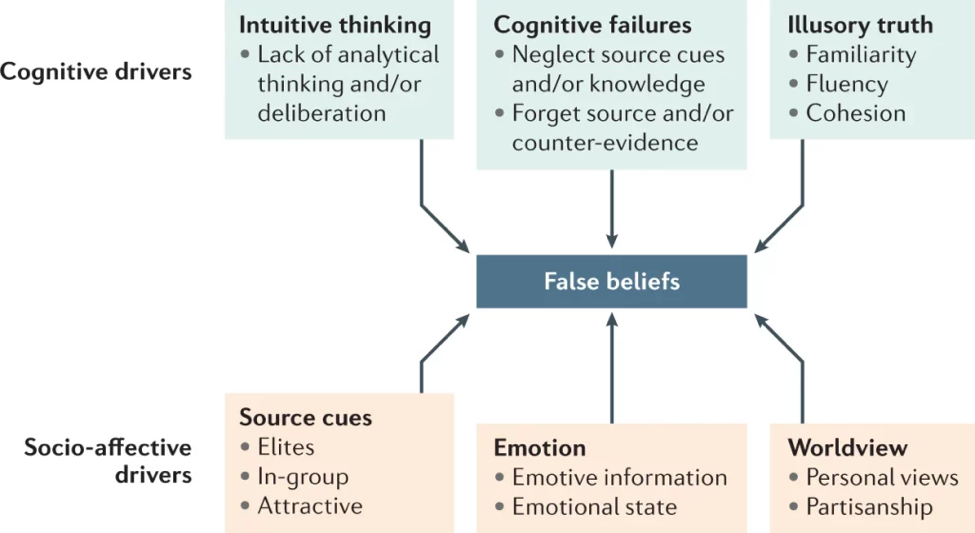

Researchers from Nature magazine provide an illustration of the factors that reinforce our belief in fake news and other false information:

Scheme of factors that influence the formation of false beliefs

We see that among cognitive factors, the most influential are: intuitive thinking, the tendency to forget the source of information and opposing ideas, as well as the illusory truth effect mentioned earlier. However, social factors cannot be ignored, as they also significantly impact the formation of false beliefs. It is worth highlighting the views of pseudo-experts and pseudo-sociology, which are often used for societal manipulation and can appear convincing without proper verification. The latter requires considerable time, effort, and expertise. We recommend exploring the database of pseudo-sociologists and hidden PR agents created by Texty.org.ua. It will help better understand which names are best avoided.

It is also important to highlight the emotional component, as one of the key factors behind the persistence and rapid spread of disinformation is the emotions it triggers. People are more likely to share emotional content.

Lastly, group membership often contributes to the formation of beliefs through antagonism toward others’ opinions. People are not inclined to change their beliefs and are often guided by biases. As a result, instead of acknowledging the possible fallibility of their judgments, especially with the support of a group and like-minded individuals, they may begin to discredit the person who challenges their views.

Reason #3: Social Media and Their Algorithms

Social media platforms and the gradual expansion of their functionality have changed our perceptions of media, news consumption, communication, and other processes related to the circulation of information in society. They have opened up many horizons for communication with friends and family, as well as helping to find like-minded individuals, build relationships with others, etc.

However, there is a downside, as social networks operate on algorithms that determine what each user will see in their feed. The algorithms track user behavior on the platform and generate content recommendations based on the user’s preferences and network activity. This can have negative consequences, as it promotes a gradual limitation of the topics shown in the news feed: the person starts consuming information in a so-called “information bubble,” because the algorithms mostly show content that matches their personal interests and beliefs. The principles behind social media are designed to show not necessarily the most quality and verified information, but content that best matches the user’s preferences and encourages interaction with posts (for example, clicking on links or ads).

Research also shows that social networks encourage us to share emotional content through the sharing function. This way, a person can express their agreement/disagreement with a certain phenomenon, outrage, or any other emotion. As a result, truthfulness, accuracy, or completeness of information takes a backseat to the emotions it evokes in us. Accordingly, users are more likely to follow the principle “The more popular this idea, the better,” rather than considering its truthfulness. This approach contributes to the spread of disinformation despite media literacy skills.

An interesting survey conducted in 2022 by Pearson Institute and the Associated Press Media Research Center revealed the following data:

(1) 91% of people believe that the spread of misinformation/disinformation is a problem,

(2) 71% believe they have been exposed to misinformation/disinformation, and of these, 43% believe they themselves may have spread misinformation/disinformation;

(3) 73% believe that misinformation/disinformation contributes to radical political views;

(4) 77% believe that misinformation/disinformation fuels hate crimes based on race, gender, or religious affiliation.

The results of the survey only confirm the thesis that despite certain media literacy skills and an understanding of the threats posed by disinformation, social media users continue to spread it. This is because it often targets the most vulnerable aspects of the human psyche, particularly the emotional component, which can often overpower rational thinking.

What can be done to counter disinformation:

- When you see information that evokes strong emotions, stop and think about what emotions it triggers in you. Look for confirmation in official sources of information. This primarily refers to reliable media outlets that adhere to journalistic standards, are transparent, and are accountable for the information they publish. Additionally, check the websites of government institutions.

One of the main objectives of disinformation is to provoke emotions in the consumer and encourage the further spread of false information. That’s why it is crucial to approach information consumption with a clear mind and understand why a particular message might be spreading.

- What are the key arguments in the publication? What is the purpose of these arguments? Do these arguments rely on facts or on abstract statements (such as “someone once said” or “British scientists researched this”)? Are they manipulating your perception?

- Think about the conclusions that this information leads to: what are these conclusions, do they encourage radical actions, or do they discriminate against a particular person or group of people?

- Analyze the source of the information – is it official? Have there been scandals associated with this source in the past? What do experts say about this source of information? Is it known who owns this media, page, community, etc.?

- Try to learn the context surrounding this message. Understanding the context in which information is presented will help you evaluate it comprehensively and avoid situations where information “taken out of context” might be misinterpreted.

- Try to identify cause-and-effect relationships: what might be the reasons this information is presented in this context? What could be the reasons certain phrases, tones, accents, and narratives are emphasized?

- Think about your opinion on this issue before you learned this information. Has it changed? If so, how?

- Try to find alternative perspectives on the issue: are there other points of view on this matter? What do experts say about this phenomenon or event?

- If you are certain that the message is false and/or intended to manipulate users’ opinions, feel free to report it to the social media administration so that access to it can be restricted.

These tips are meant to help you better understand and evaluate why a particular source is spreading such messages. This will help you become more resilient to disinformation and improve your media literacy.