Imagine a world where no corporation has a monopoly on your data, where users control their own online interactions, and where the rules of the digital space are set not by large platforms but by you. This is not just a dream of techno-utopians — it is a reality that decentralized platforms are gradually bringing to life.

The modern Internet, as we know it, was once an uncharted space where every user could be not only a consumer but also an active participant in its development. However, over time, this world changed. The era of large centralized platforms (Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, TikTok, and others) brought convenience but also unprecedented control over our personal data and online lives.

Now, a new trend is emerging on the horizon — a return to decentralization, which promises to change the game. Decentralized platforms, once considered an exotic niche for tech specialists, are beginning to gain popularity among a wider audience.

What challenges and issues with Big Tech are driving the search for alternative platforms? What are decentralized social networks, how do they differ from Big Tech, and can they become a viable alternative? These and other questions are explored in an analysis by the Center for Democracy and Rule of Law.

The First Steps Toward Digital Freedom: How It All Began

In the early days of the Internet, communication was largely based on decentralized models of information exchange. This meant that ordinary users had the ability to participate in the distribution and management of information flows. Content moderation was largely in the hands of users themselves rather than platform owners. One of the most striking examples of such a decentralized model is Usenet (User’s Network), created in 1979.

Usenet is one of the oldest communication systems in computer networks, allowing users to exchange files and messages through dedicated servers (nodes). These servers followed a shared set of rules for computer systems to interact with each other — the UUCP data transmission protocol (later NNTP).

Usenet functioned similarly to an online forum, where users could discuss various topics in so-called “newsgroups”. One of its unique features was the absence of a unified content management policy, centralized control bodies, or professional moderation teams. The responsibility for moderating newsgroups rested with their creators, who independently determined the rules for managing their groups. However, content moderation was not very effective. It was done manually, and each new user post required moderator approval before being published.

At first, the lack of effective content moderation tools was not a major issue, as most users were academics interested in maintaining their professional reputations and adhering to generally accepted netiquette norms. However, as Internet access expanded in the 1990s, Usenet transformed into a global network used by a diverse range of people, making it increasingly difficult to maintain these unwritten netiquette standards.

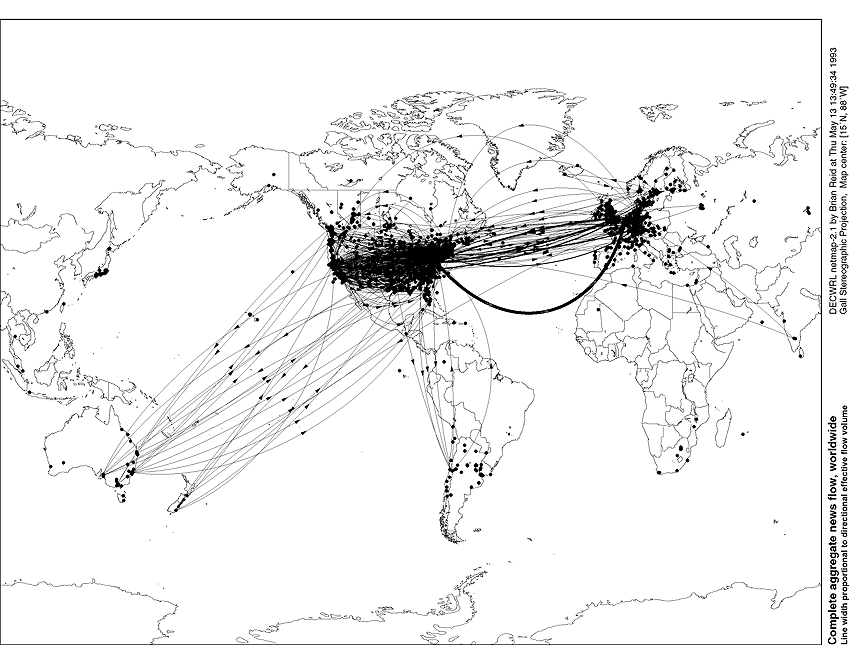

A Map of Information Flow in Usenet in 1993

Source: Vox

Over time, Usenet faced a significant problem: mass distribution of unwanted messages and spam. Attempts were made to solve this issue by blocking specific users and filtering content from servers with excessive amounts of spam, harassment, or other undesirable material. However, these measures proved insufficient to maintain a safe online environment, ultimately leading to a decline in Usenet’s popularity.

As the Internet rapidly developed and became commercialized in the 1990s and 2000s, larger communication platforms with extensive resources began to emerge, gradually displacing Usenet. These new platforms had a centralized structure, allowing for better content control and enhanced user safety. For example, companies like Facebook, which launched in 2004, and YouTube, founded in 2005, became among the first major centralized platforms where content was managed centrally according to standardized rules.

Thus, the rise of centralized platforms was driven by the need for more effective content management and improved user safety — something that decentralized models like Usenet struggled to provide. While Usenet left a lasting mark on Internet history, its role gradually diminished in favor of centralized platforms, which (at least at first glance) appeared to be more successful in addressing challenges related to content moderation, control, and security.

The Big Tech Revolution and the Rise of Centralized Giants

The mid-2000s marked the beginning of the era of private, centralized platforms. Initially, Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter (now X) emerged, followed by Instagram, WhatsApp, TikTok, and other centralized services, which rapidly integrated into our daily lives and became dominant in most users’ Internet activity.

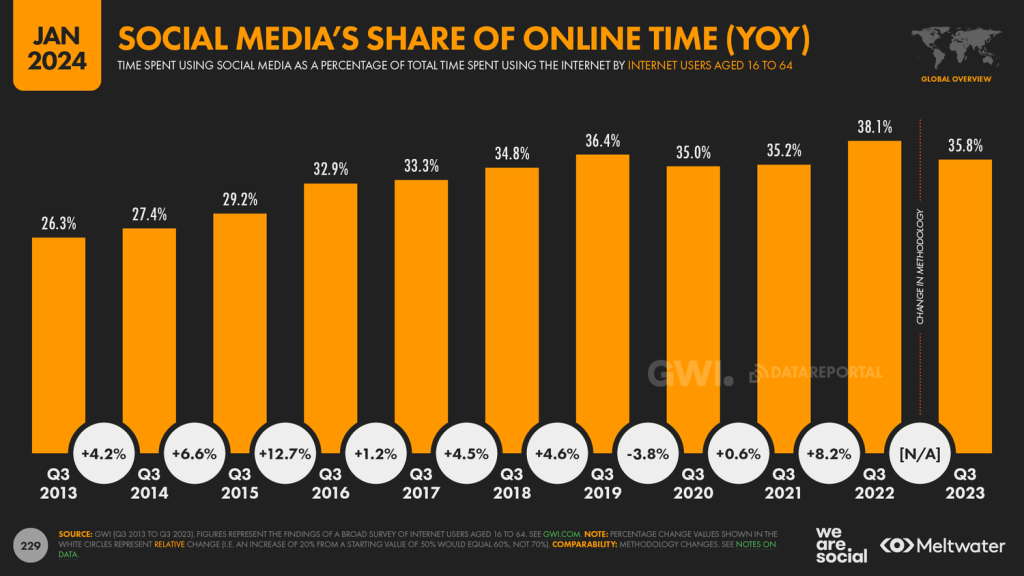

According to Datareportal, as of today, 35.8% of all our daily online activity occurs on social media—meaning that every third minute we spend on the Internet is within a social network.

Source: Datareportal

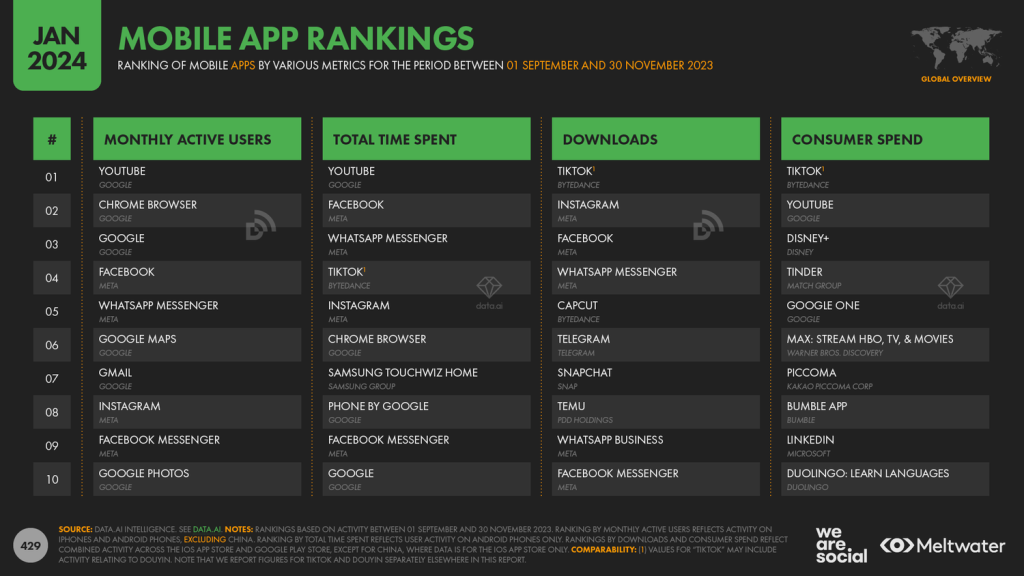

If we look at which social networks are the most popular among users, the list is dominated by large centralized Big Tech platforms. Primarily, this includes YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, and Instagram.

Source: Datareportal

Large centralized social media platforms have several distinct characteristics that differentiate them from decentralized platforms and present specific challenges:

1. Closed Internal Internet Data Transmission Protocols

Centralized platforms operate as large servers, using standard Internet data transmission protocols for user interactions. However, their internal protocols remain closed. For example, there is no open data transmission protocol for Instagram that would allow you to create your own Instagram server and simultaneously communicate with other Instagram users on Meta’s servers.

What Would an Independent Server Provide? An independent server would allow you to establish your own content management rules, data protection policies, and manage them independently. However, due to the technical structure of centralized platforms, this is not feasible.

2. Technical Limitations of Closed Protocols

The technical specifics of closed protocols prevent users of one platform from interacting with users of another platform.

For example, from your Instagram account, you cannot directly message or share content with users of other platforms such as Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), or TikTok. This is because each platform has different closed internal data transmission protocols — they “speak” different languages.

3. Surveillance Capitalism

The business model of tech giants relies on collecting and utilizing as much user information as possible. This data includes:

- Information that users consciously and intentionally share with the platform when accepting terms of service.

- Data that users unconsciously or unintentionally reveal through their behavior on the platform, such as search queries, likes, comments, and other interactions.

User data acts as a form of payment for using the platform’s services. Companies use this data to create user profiles, predict behavior, target advertisements, and more. The large-scale collection and use of personal data is referred to as surveillance capitalism.

4. Centralized Data Privacy Management

The vast amount of collected data requires strict protection by social media platforms, which implement centralized policies and processes to safeguard user data.

However, any breach of privacy can have serious security consequences, exposing users to potential abuse. A prominent example is the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

In 2014, this company illegally accessed the personal data of 87 million Facebook users via the app “This Is Your Digital Life”. The obtained data was used for political targeting during the 2016 U.S. presidential election and the Brexit campaign in the UK. This incident exposed significant flaws in Facebook’s data protection practices and led to widespread controversy.

5. Centralized Content Moderation

Big Tech companies regulate more user interactions than any government ever has. They review billions of content pieces daily and independently decide what and how to regulate.

Although most content is harmless or beneficial, social networks are also used to spread harmful content, such as hate speech, misinformation, and fraud. Platforms take measures to counteract such content by: removing harmful posts, adding warning labels, fact-checking, adjusting algorithms to limit visibility, temporarily or permanently banning violators.

Tech companies aim to create a safe and monetizable environment, which is why they invest heavily in content moderation. For instance, after the 2016 U.S. elections, Meta spent over $13 billion on security and hired 40,000 employees for content moderation. AI-based moderation tools now allow the automatic detection and removal of billions of fake accounts and harmful posts.

Content Moderation as a De Facto Government

Platforms effectively perform the functions of all three branches of government:

- Legislative: They create their own rules and community standards.

- Executive: They enforce these rules via moderators and AI algorithms.

- Judicial: They handle appeals regarding the enforcement of their policies.

Even in social media groups or pages, where administrators have some control, they must still comply with the platform’s general guidelines. The high centralization of power in private companies raises concerns among experts about its impact on human rights and digital security.

Additionally, the vast scale of content moderation leads to inevitable errors:False positives: Content that does not violate rules is mistakenly removed; False negatives: Harmful content remains online due to moderation mistakes. Platforms acknowledge making hundreds of thousands of errors daily.

6. Global Reach

Large centralized platforms operate on a global scale, connecting users across countries and cultures. This enables:

- Communication and collaboration across borders

- Discovery of like-minded individuals

- Participation in global discussions

However, global operations also pose challenges. Social networks must navigate different languages, cultures, laws, and norms. What is acceptable (or even legal) in one country may be unacceptable (or illegal) in another.

To address this, Meta developed the Trusted Partner network, involving over 400 civil society organizations worldwide. In Ukraine, the CEDEM organization is Meta’s trusted partner, helping users recover wrongfully blocked content and accounts since the start of the full-scale war.

Despite efforts to accommodate regional differences, platforms often struggle to properly adapt to local contexts. Additionally, platform interfaces and rules are not always available in all languages, creating barriers for users.

7. Attention Economy

Human attention is a limited resource. Since there are only 24 hours in a day, social platforms compete not just with each other, but also with:

- Friends and family

- Hobbies

- Even sleep

This competition can negatively impact users’ well-being. Social media platforms strategically analyze user behavior (likes, searches, watch history, etc.) to capture attention at the right moment and display advertisements.

Thus, the business model of centralized social networks is based on monetizing user attention. While users do not pay money for these services, they “pay” with their data, time, and attention.

The Rise of Decentralization

As Big Tech platforms concentrate too much power, concerns are growing about the balance between their business interests and human rights.

This has led to increasing discussions about alternatives to centralized platforms, particularly the Fediverse (short for “federated universe”).

What Is the Fediverse?

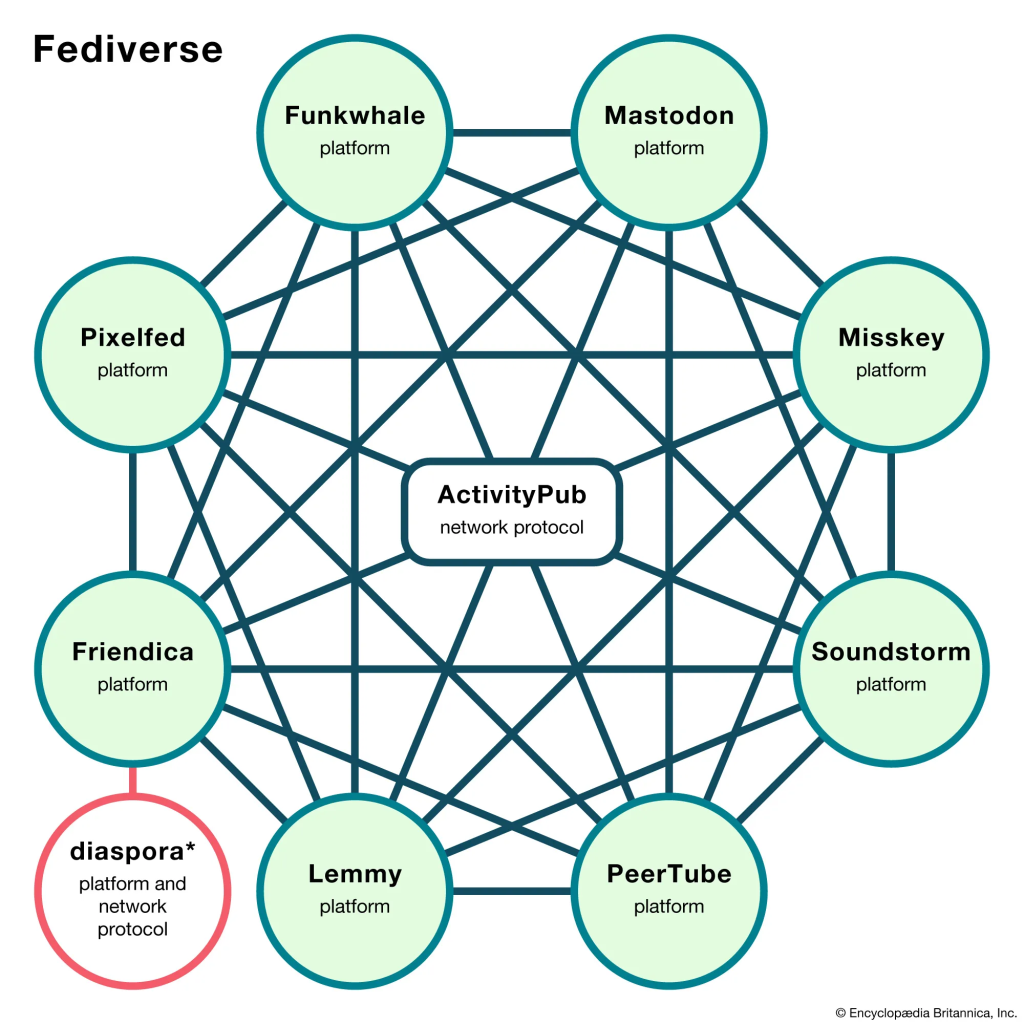

The Fediverse consists of over 100 decentralized platforms that communicate using a common open protocol: ActivityPub. This enables cross-platform interactions, such as:

- Sending messages

- Sharing content

- Following users across different platforms

How Does It Work?

A useful analogy is email:

- Gmail users can email Yahoo or Outlook users, even though they use different services.

- Similarly, decentralized social networks communicate across platforms using the same open protocol.

For example, a user on Friendica (Facebook alternative) can interact with a user on Mastodon (Twitter alternative), even though both platforms have different content policies, interfaces, and functions. If a user dislikes Mastodon, they can switch to another platform without losing their followers or content.

This interoperability is possible because the Fediverse operates on open-source, decentralized protocols, primarily ActivityPub.

A Brief History of the Fediverse

- 2008: Identi.ca, a decentralized Twitter-like platform, was launched using OpenMicroBlogging (OMB).

- 2012: The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) started developing OStatus, which became widely adopted.

- 2014: W3C shifted focus to ActivityPub, which was officially recommended in 2018 and is now the primary Fediverse protocol.

Thus, the Fediverse offers an alternative social media ecosystem that prioritizes openness, interoperability, and user control over data.

Source: Encyclopædia Britannica

The image shows the most popular decentralized platforms of the Fediverse, each of which serves as an alternative to certain Big Tech platforms, such as:

- Mastodon – a decentralized social network that serves as an alternative to Twitter. It allows users to post short messages, follow other users, and interact through likes, reposts, and more.

- Pixelfed – an Instagram alternative focused on photo sharing. It offers features for posting images, following other users, and interacting through comments and likes.

- PeerTube – a YouTube alternative that allows users to upload, watch, and comment on videos.

- Funkwhale – a Spotify alternative that lets users listen to music, create playlists, and share music with others.

- Lemmy – a Reddit alternative, this platform enables users to create communities, discuss various topics, post content, upvote posts, and comment on them.

- Misskey – another decentralized social network similar to Twitter, with additional interactive features such as emoji support and special reactions.

- Friendica – a Facebook alternative that allows users to create profiles, communicate with friends, post statuses, share photos, and exchange messages.

These platforms are integrated through the ActivityPub protocol, allowing them to interact with one another—for example, Mastodon users can subscribe to PeerTube channels from their Mastodon account and see PeerTube videos in their news feed. This creates a decentralized but interconnected ecosystem of platforms.

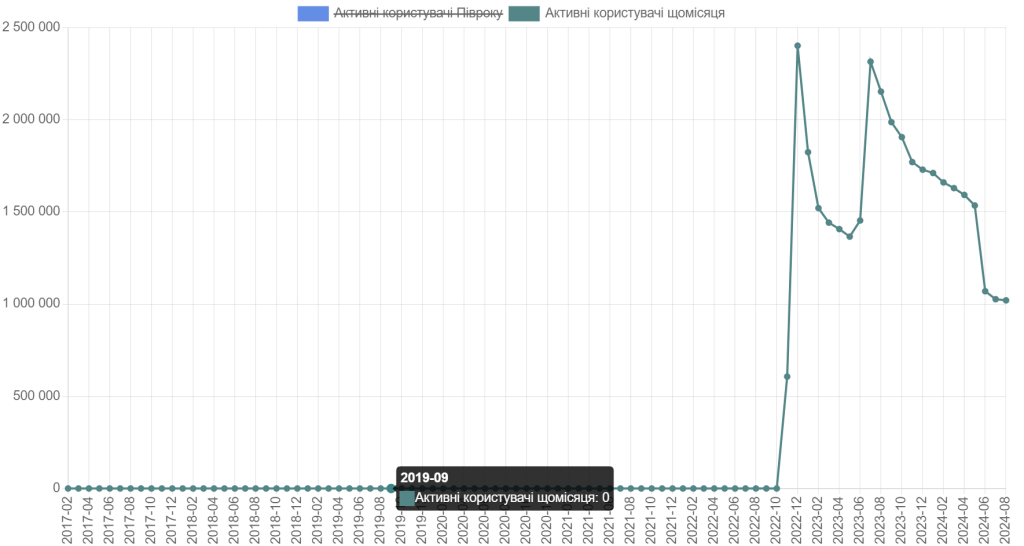

Fediverse platforms began gaining international popularity in 2022. After controversial changes at X (formerly Twitter) following Elon Musk’s acquisition of the platform, many prominent civil society figures, human rights activists, celebrities, and former X users and employees migrated to Fediverse platforms. Mastodon, in particular, saw a major surge in users—from around 400,000 in late October 2022 (before Musk’s acquisition of X) to nearly 2 million in mid-November (after the acquisition). However, after this initial spike, the number of users on Fediverse platforms plateaued. Since then, the number of active monthly users has dropped by half.

The average number of all active Fediverse users per month.

Source: Fediverse Observer

One of the main challenges in building a sustainable user base for the Fediverse is that people use social networks because of the network effect (whether their friends are there or not), rather than ideological beliefs (centralized vs. decentralized platforms). Since relatively few people use Fediverse platforms, they have low network effects, meaning few of our friends are there. As a result, we continue using centralized social networks where we can stay in touch with more people.

Additionally, centralized social networks are much more user-friendly since they have spent years refining their interfaces based on feedback from millions of users. Navigating Fediverse platforms can be difficult for new users at first, creating a barrier to adoption.

Other challenges include:

- Lack of regulatory clarity

- Uneven content moderation quality across different servers

- Limited funding for servers

- Resource constraints and other operational difficulties

Addressing these challenges requires a systematic and gradual approach, including:

- Improving user interfaces and experience

- Enhancing content moderation

- Raising public awareness about the benefits of the Fediverse

Fediverse Growth and Comparison with BigTech(more than a hundred platforms)

As of July 2024, there were approximately 12.1 million accounts across over a hundred Fediverse platforms, with about 1 million active monthly users. However, this number pales in comparison to Big Tech platforms:

- Facebook – ~3 billion monthly active users

- Instagram – ~2 billion

- YouTube – ~2.5 billion

- TikTok – ~1.6 billion

That said, Fediverse platforms are still evolving, and their user base has grown significantly compared to two or three years ago, especially after the 2022 boom following changes at Twitter (now X).

The Fediverse and Ukrainian Users

Among Ukrainian users, Fediverse platforms are not among the most popular social networks. Instead, Telegram, YouTube, Facebook, Viber, Instagram, TikTok, and X dominate.

However, after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, interest in decentralized platforms (especially Mastodon) increased. While Big Tech platforms (especially X and Facebook) imposed restrictions on sensitive war-related content, some Ukrainians started exploring alternative platforms for communication and information-sharing.

Mastodon, in particular, has servers hosted in multiple Ukrainian cities, including Kharkiv, Kherson, Khmelnytskyi, Kyiv, Mykolaiv, Odesa, Rivne, Poltava, and Lviv. Each server is typically thematic, bringing together people with similar interests or from a specific region. They have unique content moderation policies and data protection rules, allowing users to choose a server that best fits their needs. Additionally, if users’ preferences change, they can easily “move” to another server while keeping their followers and important data.

Current State and Future of the Fediverse

Despite its relatively small but stable audience, the 2022 boom proved that people are interested in:

- More control over their content and data

- Avoiding centralized control from major corporations

- Freedom to choose moderation policies that align with their values

The lack of centralized moderation and growing dissatisfaction with Big Tech’s controversial policies make decentralized platforms an appealing alternative. However, to attract more users and build a larger, sustainable community, these platforms must:

- Improve the user experience

- Explain the benefits of decentralization (such as more control over policies and better data privacy)

Conclusions

In a world where the internet and online platforms are cornerstones of modern society, the question of who controls these platforms is becoming increasingly important.

The history of digital ecosystems shows a shift from early decentralized models (like Usenet) to today’s Big Tech dominance. However, Big Tech’s growing influence has led to concerns over privacy, data control, and freedom of speech.

Today, we are witnessing a gradual return to decentralization, with the rise of Fediverse platforms offering:

- Greater autonomy

- More control over data storage and communication

- Freedom to choose content without corporate algorithms interfering

However, these platforms face significant challenges:

- Weak network effects – most people use social networks because of their friends, not ideological beliefs

- Less intuitive interfaces – Fediverse platforms are often less polished than Big Tech alternatives

- Uneven content moderation – different servers have different rules and resources

- Limited funding and technical resources – making it harder to compete with well-funded corporate giants

Overcoming these obstacles requires technical improvements, community engagement, and broader education about decentralization. This is a long-term process that demands both time and resources.

For now, decentralized platforms remain a niche alternative, primarily attracting privacy-conscious users and tech enthusiasts. However, their potential to reshape the digital landscape is undeniable. Their success depends on finding a balance between freedom and usability. Without that, decentralization risks remaining a fringe movement rather than a true challenge to Big Tech’s dominance.