People are fighting and dying online,

they are singing and dying, delivering press releases

and dying, laughing and dying, and singing once again.

And the whole world can do nothing about it.

@kulchytsky about Azovstal

Previously, movement of military forces, losses, surrenders, or the signing of peace treaties were covered at least a few hours after such events occurred – from press reports during the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848 to the two world wars and numerous regional conflicts on radio and television. Today, civil disorders, large-scale disasters, and tragedies get in the public domain faster than we learn about their outbreak. Social media archives store the stories of eyewitnesses, but these platforms are no longer the diaries of events – they are becoming a driving force more and more often. Just think of calls for genocide in Myanmar, violence against refugees in Germany, riots in the US Capitol, and many other cases when the online platforms became a chessboard…

We have talked a lot about the use of social media by terrorists (you can read about it here, here and here) and the difficulties of countering other non-state actors (armed insurgents, organizers of armed riots), touched on issues of jurisdiction and blocking, regulation of hate speech, etc. Analyzing these topics, at the very least, one can conclude that States are capable of seeking solutions, reaching compromises and cooperating with the tech giants. But is a similar approach possible in the “fog of war”? During an armed conflict, communications get transformed: they are affected by the regime of States’ derogation from obligations under international treaties, the applicability of humanitarian law, and the frequent changes of the actor exercising effective control over the territory. This pushes social media to the brink of legal collapse — when any action ultimately leads to human rights violations, the threat of conflict escalation, and the subsequent deaths of hundreds of innocent people.

This was first seriously discussed during the Arab Spring, with social media contributing to the mobilization that led to the intensification and rapid unfolding of the conflict. Subsequently, the platforms played an important role in the conflict in Ethiopia in 2020, where ethnic animosity was only fueled by Facebook and Twitter posts. Platforms were also involved in the armed conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia, the situation in Afghanistan, the conflict in Syria, and many other wars, international and civil ones.

Against this background, the fact that about 48% of the US adult audience uses social media as a source of news is important. In Ukraine, just a month before the full-scale invasion, authorities announced the distribution of smartphones among the elderly – digitalization in action. Social media are one of the main sources of information about military actions both abroad and inside the country. How exactly do the platforms influence the course of the war?

- Direct communication with the population. On the one hand, during the war, promptly available messages from the State authorities prevent panic (for example, Zelenskyi’s stream from downtown Kyiv on the morning of February 24), simplify the evacuation and delivery of humanitarian aid, and help report updates in a timely and brief manner. On the other hand, as the International Committee of the Red Cross (hereinafter referred to as ICRC) points out, communication is carried out by both sides of the conflict, which makes it possible to manipulate the behavior of the population to gain military advantage, to discredit and blackmail the population, to spread disinformation and calls for violence. Moreover, unlike traditional media, no one exercises editorial control on social media, so in contrast to reassurances from the State, it is easy to rock the panic boat “from below” by spreading “sensational news,” exaggerating facts, or manipulating readers’ opinions. No one can control this (especially given the anonymity function!).

- Effects on the distribution of forces. The party with more funds for information campaigns is able to mobilize more participants in military formations, as well as to communicate more successfully with occupied territories. Governments become adaptive to new platform functions: They use targeting to spread propaganda, create fake accounts and closed channels, etc. For example, Russians use fake bots on Telegram to gather intelligence information. Thus, social media indirectly influence the planning of military operations, delivering messages about the threat of airstrikes, the place and time of evacuation.

- Risks to peacekeepers and humanitarian aid. Threats to the employees of international organizations, dissemination of disinformation about the places where humanitarian aid is distributed, and even false information about the involvement of humanitarian organization staff in terrorist activities (for example, in Syria this led to the death of volunteers) are just a few examples of the abuse of social media to influence the course of the conflict and to prevent international aid. As a consequence, often it is only the civilian population that suffers.

- In the end we come to the question of lawfare (see the analysis of this phenomenon during elections here): alternative facts (for example, after the downing of the Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17, thousands of posts with mutually exclusive evidence of this violation appeared on Twitter), the spread of disinformation, the abuse of legal concepts to justify armed aggression or violations of the rules of war (Russia is currently abusing the concepts of humanitarian intervention and the responsibility protect to justify the war against Ukraine). All this is simplified thanks to social media, because it allows important messages to be lost in news streams, as well as to blur the boundaries between official and unofficial sources of information. As a consequence, ordinary readers cease to distinguish between truth and fiction.

In addition, astrologers predict the development of military operations, celebrities record tearful addresses with wishes for peace, young people start trends with dances in support of Ukraine… In this regard, the Wall Street Journal called the coverage of events in Ukraine “operating 24/7 war room”, referring us back to the epigraph of this piece – the wars have turned into a live broadcast.

And while from a sociological point of view, the debate can be very long, and military experts have trouble predicting when sensitive information will be leaked online again – legal qualification should not be delayed. The fact is that non-state actors – social media – have become leading players in the deployment of armed conflicts, thereby generating many legal conflicts. Can this be addressed in any way and what should the States do? Let’s look into it.

Episode I: The Phantom Menace

The Digital Services Act of the European Union (a document regulating the activities of Internet intermediaries) is looming on the horizon, a lot of national legislation is being developed (including a media draft law in Ukraine), but globally the social media are still a ‘wilderness’. The problem of the involvement of social media in armed conflicts is divided into two parts: the general legal dilemma of their status and specific gaps in their activities (the practical application of national legislation and community standards).

The problem with legal status is primarily related to the jurisdiction of States over social media (or, more precisely, its overwhelming absence). For example, Meta or Twitter are often not registered in the States in conflict – they do not even have a legal entity status. As a consequence, national regulation on freedom of expression, privacy and other issues is simply unenforceable. As are any avenues for accountability. So, here is the situation we find ourselves in: social media or messaging platforms are de facto operating in the State, creating a space for spreading calls for war or hostility, and it’s impossible to hold them accountable. Because de jure they do not exist in the State at all. Even in cases where regulation does exist – as a general framework – it will not be always possible to enforce it. After all, establishing a legal relationship with the tech giants and forcing them to open regional or, even more, national offices is an almost impossible mission. What kind of conclusion can be drawn? Social media respond to armed conflicts and regulate information on the platform when they themselves see benefit, not when a new law appears in one of the States (the EU market can be considered a rare exception).

Now let’s find out if the internal rules of the platforms offer an adequate response to the context of war. And more simply, are the platforms willing to intervene in what is happening in the geopolitical arena?

|

Disclaimer: each platform, depending on its functionality, audience in the region, internal policies and focus, responds differently to armed conflicts – the intensity of response, moderation and level of communication with local communities differ. |

Therefore, this study is aimed more at determining the average context and situation than at finding a universal model applicable to any social network active in conflict-ridden regions.

The first stumbling block does not take long to find – it concerns the definition of the type of conflict. For social media, the whole dilemma lies in the mysterious phrase ‘international humanitarian law’. Two questions arise at once: should social media deal with it at all, and why is it needed?

- Let’s start with the first one. In theory, platforms should not care how exactly humanitarian law works, because they are obliged to observe the principle of net neutrality (read about this phenomenon in Internet access here) – that is, treat everyone who uses the service equally. It makes no difference whether it is the audience of the aggressor country or the defending country. This is in theory. In practice, everything is much more complicated, because conflicts occur not only between States (and not only between two States). There are armed conflicts involving non-state actors (e.g. terrorist groups), there are civil wars, peoples struggling for self-determination, and in general – imagine social media operating during the NATO invasion of Yugoslavia.

- And here we approach the second question: why bother with such subtle concepts at all? The types of prohibited content are the same for everyone (calls for war, discriminatory statements, hate speech, etc.) – social media delete such content, no matter who posts it. Is it worth bothering about the status of the author? Yes, it is. The problem is that the parties to a conflict often qualify it in different ways. For example, as a general rule, you cannot interview terrorists or share their content on platforms. But who determines whether certain activities are terrorist activities and whether individuals are terrorists? This often becomes problematic even for the States (for example, the US failed to designate Russia as a terrorist State), not to mention social media. Moreover, the platforms themselves emphasize that they are not authorized to solve complex legal issues or regulate such matters in detail, because there are other actors for that (States, international organizations, etc).

A similar dilemma existed regarding the qualification of intervention in Donbas in 2014-2015, when evidence of the Russian presence was insufficient to prove their effective control of the territory or groups operating there. Therefore, Russian propaganda was not considered an aggressor country narrative by most tech giants. There is also a difference between the rhetoric of the aggressor State and the defending State. The latter, for example, even if it collects donations for the armed forces, does so not for the purpose of starting the war or continuing violence, but to exercise the right to self-defense (i.e. legitimately and justifiably). In the same way, determining the type of conflict and the aggressor helps to establish the sources of threats – whether the national government violates human rights and such policies must be stopped (and, therefore, requests from the State may be an attempt to censor online space), or vice versa – the State is trying to ensure public order and protect its sovereignty (therefore, requests to social media are an attempt to save the situation). The main task of the platform is to identify the main actors and their goals. Both the level of cooperation and the level of moderation depend on this decision.

In addition to a general awareness of humanitarian law concepts and types of conflicts, social media must also take into account the context on a case-by-case basis. It is impossible to create a one-size-fits-all solution or policy that applies to all situations. It is possible to draw conclusions and track the consequences of actions in different cases, but it is unlikely that the scenario that was once effective in Myanmar (and vice versa) will work in Ukraine.

Another problem with the knowledge of humanitarian law is its partial application by social media. This can be clearly seen in the issue of coverage of POWs, where platforms quite literally apply the prohibition stipulated by Article 13 III of the Geneva Convention (prohibition of public distribution of photos of POWs if such images undermine their dignity). Thus, for a long time, the social media would remove any such material, even if it concerned press conferences with POWs (which, in fact, is legal content). This means that the platforms have not fully figured out how to apply this rule, which has led to numerous restrictions on completely legal content.

And this is just one of the many issues regarding the application of humanitarian law to social media activity. Another one is the indirect participation of civilians in armed action: For example, civilians collect and transmit information about the deployment of enemy armed forces, raise funds for military equipment, conduct cyberattacks, etc. Most of these issues are debatable in terms of humanitarian law – civilians can only become a legitimate target if they are directly involved in armed hostilities. However, the ICRC and NATO point out that modern conflicts are very multidimensional, so social media often provide a significant military advantage by disclosing information (geolocation, number of troops or equipment, etc.). As a conclusion, the answer to the question about the need for platforms to have the knowledge of humanitarian law is unequivocally positive. And this makes their activities even more complicated from a legal standpoint (given that they do not use the law of a particular State or international law as a source of duties – it is mostly done voluntarily).

“Arbiters of Truth”. Behind the epic title hides a rather lengthy discourse about whether platforms even have the right to evaluate content in their own right. Thus, by qualifying a post as hate speech, the social media are effectively criminalizing the author without a court judgment (hate speech is a criminal offense). In the context of an armed conflict, the problem is clearly larger. It’s not just a matter of quickly removing clearly illegal content (such as calls for violence or war).

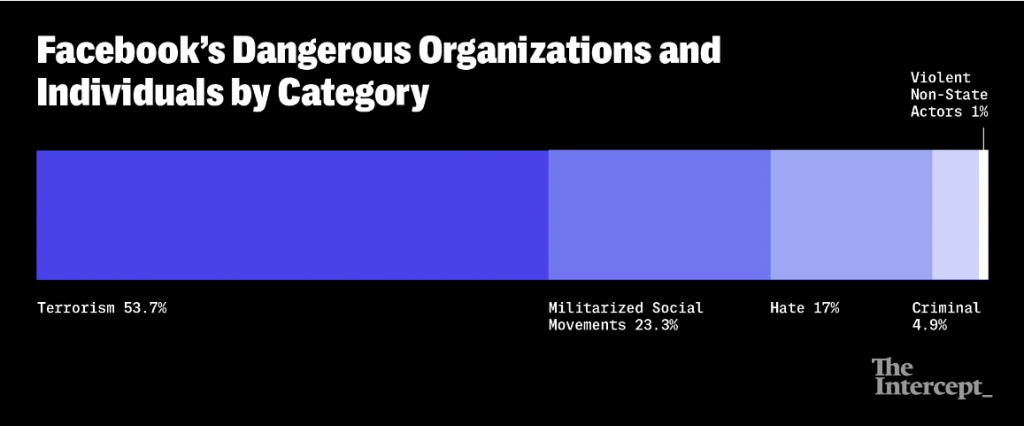

For example, we can mention the discussion about terrorist organizations and who can give any group that status. Back in 2012, Facebook added a ban on organizations associated with terrorist or violent activities to its terms of use. First of all, in forming such lists, Meta is guided by the US approach, which is often not objective (not least because it is based on the legal and cultural tradition of only one State). Moreover, despite the recommendations of the supervisory board, the company does not publish the list of organizations, indicating only the percentage (see below).

Therefore, sometimes it is not even possible to check whether the organization mentioned in the post belongs to the list of banned organizations. Meta has its own guidelines by which you can potentially assess the danger of specific communities, but such criteria are very generic, and are often applied in practice completely incorrectly. For example, in the Ukrainian context, the Azov Regiment is considered a dangerous armed group by Meta. As a consequence, any visual mention of their symbols leads to the blocking of posts, and sometimes even accounts. Underage soldiers (a 14-year-old Kashmiri), about 200 musicians, television stations, video game manufacturers, Goebbels and Mussolini are also listed as dangerous individuals and organizations. Leaving the funny cases aside, however, we come to the below conclusion: the platform determines for itself who is acting legally and who is not. And given that 53.7% of accounts have been deleted as terrorist, a logical question arises: hasn’t Meta become an international actor assigning terrorists status?

On the other hand, let us imagine that really illegal groups establish their own ‘authorities’ and have their accounts on Meta or Twitter. Should platforms verify such accounts (give a blue check mark to the account)? Do they have the right to do so from the point of view of public international law? If this discussion seems too theoretical, think of the accounts of the self-proclaimed DPR and LPR in various social media. However, to make this discourse less about Ukrainian, it is worth mentioning the situation in Myanmar. There, armed groups used the platforms to present their own political agenda and even tried to promote narratives about the formation of new authorities. Doesn’t leaving such accounts available on social media and verifying them legitimize the activities of armed groups? In contrast, can the social network itself determine who is to blame for the conflict? Facebook eventually removed about 70 accounts after civil society organizations reported their wrongdoing. But this situation means only one thing: adequate qualification is impossible without cooperation with non-state independent actors. Why so?

TikTok verifies accounts that are “authentic, unique, visible, active, and follow the community rules.” Almost all advanced social media follow a similar approach. Except for the criterion of “visibility” – a fairly large audience – the accounts of dangerous organizations may well be verified on all grounds (they will clearly start spreading the content that violates the rules of the community after receiving a blue check mark).

An example of a verified account

In fact, even verified accounts can post banned content – just to mention the case of Trump’s account blocking. That is, general rules are insufficient and require more active involvement of platforms, review of verified accounts and monitoring of their activities. And we’re back to the question of whether social media have the right to block presidents, government agencies, and designate communities as dangerous or terrorist. There is no official answer to this question, and consequences arise from time to time across the globe.

Geolocation. This social media function generates quite a number of problems in the context of armed conflicts – from violation of the principle of impartiality of platforms to direct damage to the course of hostilities.

- Firstly, geolocation affects the content in the feed. A Norwegian company once conducted an excellent research by creating two TikTok accounts: one with Belgorod geolocation, the other with Kharkiv geolocation. Subsequently, the researchers checked which posts the platform automatically showed and noticed that Russian geolocation reduces the amount of news about the war in Ukraine by almost 90%. A similar problem existed with the Russian social media outlet VKontakte, which used geolocation to identify people from Ukraine at the start of the war in 2014-2015 and target them with pro-Russian propaganda. So, the very fact of geolocation in one region or another significantly shifts the focus of information consumption.

- Secondly, and this problem is partly derived from the previous one, the “echo chamber effect”) occurs – when individuals, being in a certain environment, stop critically evaluating information from the outside. This way radicalization is taking place, because polar opinions in the feed only confirm the correctness of their own narratives. What does geolocation have to do with it? Some groups, especially political ones, often add only those individuals that have the geolocation of a certain region – city, country or continent. This allows for an audience susceptible to certain narratives. Needless to say, more often than not, this creates effective channels for propaganda.

- After all, geolocation plays an important role in planning military operations. For example, when images of destroyed buildings are published immediately after shelling, geolocation enables the other side of the conflict to adjust their fire, which can lead to more casualties (especially where the side of the conflict violates humanitarian law regarding the distinction between civilian and military facilities). Unlike Fenton’s photos from the Crimea in the 1850s, which were published weeks after the armed clashes and therefore did not cause any harm, the publication of news with reference to a specific place a few minutes after the shelling causes significant damage. A similar problem arises during “live broadcasts” on social media – this often reveals military positions in real time. As a consequence, the other side of the conflict can reschedule offensive actions (again, back to the question: Do any such live streams play a direct role in hostilities?).

Advertising. This problem might be the easiest to solve – you just need to ban advertising in the crisis-ridden region. For example, political ads were disabled by Google and Facebook on the eve of the 2020 US presidential election to prevent disinformation, manipulation and breach of silence. Twitter added the function of marking ads as sponsored by a specific person (Meta has now adopted this algorithm as well). During the war in Ukraine, TikTok also turned off the advertising function – the company mentioned this on its website, emphasizing that this was done for security reasons. Indeed, advertising campaigns are very dangerous in times of war, as they provide an effective means of spreading disinformation, hate speech and calls for violence. Moreover, microtargeting allows identifying the interests and views of specific individuals in order to directly influence their decisions. In the context of war, this opportunity serves as an additional weapon in the hands of the aggressor. For example, it will make it possible to convince the population of the occupied territories that the aggressor country is winning or that after the deoccupation everyone will be held accountable as collaborators. As a consequence, support for the aggressor will grow.

By the way, blocking the advertising function as such is the only measure that did not come in for a lot of criticism from international human rights organizations. The only comment was a demand to develop an adequate mechanism for blocking advertisements – that is, not to tie them to keywords or expressions, but instead to limit this possibility for specific actors.

In some cases, only ads from a particular region are blocked. For example, Google blocked about 8 million Russian ads in connection with the aggression against Ukraine. Some of them were directly sponsored by the State. Meta also banned only the ads sponsored by State media (or media controlled by Russian authorities), while Twitter most often blocks ads regionally. YouTube has taken a more balanced approach, limiting its advertising options for the channels that are directly connected with the aggression or can be engaged as a means of propaganda. Overall, the distinction is very important because a defending country is less likely to spread war or violence propaganda. At the same time, the advertised posts often contain useful information for refugees, victims, and volunteers. Advertising is also important for small and medium-sized businesses – because this industry suffers the most in a country suffering from military attacks.

However, we should bear in mind that social media still have a business model, and such decisions significantly impact on their income. For example, after the introduction of ad blocking for Russian media, the Russian government announced Meta and YouTube blocking. A little later, Twitter suffered the same fate. Moreover, the government even declared Meta an “extremist organization” (by the way, should Meta block itself from the platform now?). Although in this case, Russia’s decision did not affect the platforms’ measures to mitigate damage in the information field, we should be aware that this will not always be the case. That is why the decision to stop advertising is quite effective for overcoming negative consequences, but a “painful” decision for the platforms themselves – they both lose profit from possible advertising and may be subject to additional sanctions imposed by the States.

Hate speech. This topic is probably worth a separate analysis, because we can talk endlessly about the interpretation of linguistic features, the replacement of words with symbols and images, sarcasm and satire (including in the form of memes). However, there are also problems directly related to the armed conflict. For example, naturally, during a war society becomes more radicalized. Especially when the war is not a dispute over neutral territory, but the aggression on the part of one of the States. As a consequence, social media in such cases become a forum for expressing fear, rage or irritation. If platforms block all persons who condemn aggression or express hatred for the representatives of the aggressor country, those who actively support or approve of armed actions – the majority of the population of the defending State, victims of the conflict, etc. will not be able to use the platform at all. As a consequence, users will not post evidence of international crimes (such as the shelling of civilian buildings) and will engage in self-censorship.

In order to avoid the so-called “chilling effect”, which is regarded as a negative consequence of restrictions, social media should regulate freedom of expression during such periods in a balanced manner. The first attempts in this direction were made by Meta, which loosened moderation policies at the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, allowing Ukrainians to call for violence against Russians, to post videos and photos of the Azov regiment, etc. However, one could subsequently see quite a lot of hesitation on the part of company representatives and statements that the new approach was misinterpreted and that hate speech should be banned in any form. Yet, the very fact of the changes has already caused a response, and it was rather ambiguous. On the one hand, human rights activists were strongly opposed to allowing calls for violence or hate speech. Many human rights organizations, on the contrary, praised the move, noting, however, that it would be worth applying the same policies uniformly to all the regions affected by the conflict.

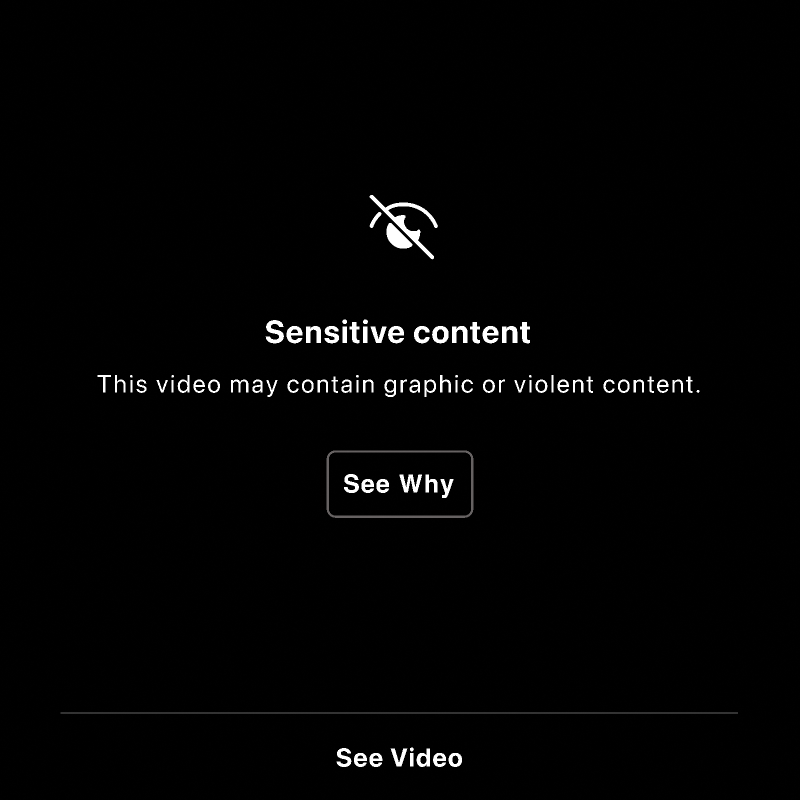

Depiction of violence. One of the fundamental differences of social media in times of armed conflict is the abundance of information about injuries, rape, violence, shelling, images of dead people, etc. This immediately raises several problematic questions: How to regulate such content if the depiction of violence on the platform is prohibited? How to regulate such content, given that the platforms can be used by minors? How to regulate such content without losing evidence of war crimes?

First of all, we should mention the update of policies on depictions of violence – instead of removing such information, platforms have started to publish “sensitive content” disclaimers, warning audiences about potentially violent content. Another option is to use the blur function for photos containing such information. Thus, the change in policy allowed the preservation of evidence of human rights violations, because this information can come from any source and at the same time this source can be a single source, and therefore the materials require special protection. But there is often controversy about the further obtaining of such evidence: For example, in The Gambia v Facebook there was a fierce debate about the protection of confidential communications and the need to obtain information for proceedings before the UN International Court of Justice.

Moreover, violence and violent stories are often a side effect of social media use by individuals from conflict-ridden regions: for instance, people are posting bomb shelter videos on TikTok, bloggers and influencers have shifted their focus of activity to support the armed forces. Given that psychological health has become a particularly hot topic since the pandemic, social media are trying to balance the need to report crimes to the world and the maximum protection for the psyches of vulnerable groups. After all, war in the era of social media affects not only the population of the country on the territory of which the armed conflict is taking place. Information from individuals telling stories of surviving a city siege, starvation or shelling is available worldwide. And not everyone is morally ready to face such reports in the news feed (especially when they are accompanied by visuals).

Disinformation. Today this is one of the most pressing issues of regulating freedom of expression, because there is still no international consensus on the actors and forms of responsibility for its dissemination. Platforms do not have an answer either. That is why each social network develops its own approach to reduce the risks of such content, especially in regions affected by conflict.

Disinformation is dangerous, because it often serves as fuel for a hotbed of war (mobilizes people, incites hostility and aggression), and also supports the conflict in its active phase. For example, in order to influence people’s minds, they often spread false information about the responsibility for not leaving the occupied territories, the parties to the conflict often give biased casualty statistics, try to hide war crimes or attribute them to the other side, etc. Also with the help of deepfakes, one side of the conflict may try to induce the other one to surrender (by influencing the population). Thus, in Ukraine, at the beginning of the full-scale invasion, a rather low-quality deepfake of Zelenskyi was distributed. But who said that sooner or later better technologies won’t come into play?

Let’s recall the echo chamber effect, which is amplified by the spread of disinformation: not only are readers in a comfortable information environment, but they are getting the data they want to hear. This confirms that they are right and sometimes even radicalizes the audience. Multiplied by the presence of algorithms favorable for this (the platform forms a news feed based on the information in which the user is interested – most often comments and likes), disinformation gradually takes over the majority of the information space. As a consequence, readers have a false sense of security, a misperception of current events or information about socially important phenomena. In addition, platforms are overloaded with information, which contributes to the dissipation of attention. As a consequence, old and new news reports are often mixed up, causing misperceptions in the audience’s mind. In the context of armed conflicts, this poses an immediate threat to human life, as false information can relate to evacuations, medical or humanitarian aid, green corridors, etc. Mistakes in these matters have a very high cost.

What answers did social media come up with? First of all, the platforms began to mark the media that are owned by Russia or are significantly controlled by the authorities. The success of this measure from a sociological point of view is still questionable. Let’s imagine that there are people who perceive Russian journalism as the only objective source of news. Will this mark on the account stop them? No, it will only make it easier for them to filter “their” and “other” sources of information. As a consequence, the information space of such people will be deprived of even the slightest chance of adequate news.

Moreover, disinformation on platforms is also spread by individuals. In TikTok, for example, many Russian influencers have said that they are paid for posts with calls for peace. This completely discredits the message in the eyes of the audience and blurs the boundaries of readers’ assessment of the war. On the other hand, many influential users do get paid to disseminate opposing views – endorsing aggression, justifying war crimes, etc. As a result, it is very difficult to distinguish between truthful information and a person’s position and paid manipulative propaganda. Given that there are fewer fact-checking tools on platforms, as well as the often distorted presentation of critical news (the race for sensationalism rather than objectivity), they become excellent breeding grounds for disinformation.

Secondly, in response to the described challenges in the Ukrainian context, TikTok suspended live broadcasts from Russia, YouTube blocked pro-Russian media channels, and Twitter created special tags for such accounts. And such responses should be viewed through the prism of general rules: Both under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the co-regulatory codes on countering disinformation and hate speech. Although these documents do not establish legal obligations, they are considered best practices for corporate regulation of freedom of expression. Thus, Meta’s policies are largely aligned with these documents, while case studies indicate that companies comply more than 70% of the time. For example, in the context of elections, Facebook tested algorithms that prioritize rational and objective sources over those that polarize society. The results of such tests, however, have not been made public, nor have there been any other announcements of similar experiments. This may suggest their relative failure.

However, there is still no comprehensive solution to the problem of false news spread. The most difficult question facing social media is where is the truth? And, unfortunately, it is not easy to find an independent actor who will say what to believe. Cooperation with States in this area often looks like the promotion of State propaganda. And in times of armed conflict this is especially dangerous, because the narratives of the warring States will be polar, and manipulation will simply be everywhere. To avoid this, platforms try to hire independent fact-checking companies. In Ukraine, for example, the fact-checking organizations StopFake and VoxUkraine cooperate with Meta. Although two organizations are clearly not enough for the territory and context of Ukraine, the use of independent fact-checkers today is the best option for an objective assessment of content.

Social media also seek help from local NGOs, which are more aware of the local context. In times of armed conflict, this is especially relevant because it helps to facilitate the truth vs. manipulation discourse. Such collaborations have already taken place in Syria, where platforms tried to prevent disinformation that undermined humanitarian aid efforts.. Local human rights activists were very quick to respond to false news and helped social media respond to activities on the platform faster and better. Of course, this is not a cure-all solution for disinformation, because the measures described are reactive rather than proactive. Preventing manipulation and false news is only possible by developing critical thinking. And this is a long and complex process.

Blocking. Sanctions are a logical consequence of the spread of hate speech and disinformation. And the first level of sanctions, of course, is the response from the platforms. First, they try to respond in a targeted way – by blocking access or removing publications that violate the terms of use. If such measures fail, the social media begin to impose sanctions on accounts or pages. For example, as a global response to the war in Ukraine, Twitter, Meta, and YouTube began blocking pro-Russian accounts that incite hatred. Importantly, NATO representatives have emphasized Russian information aggression since 2014, as has ex-President President Poroshenko. We saw a noticeable response only after February 24, 2022. A similar intensity of reaction was observed in Myanmar – most of the measures were introduced by social media later, after the conflict began.

However, such measures are applied in both directions – and here a problem arises, because the accounts of Ukrainians are also often blocked. Thus, Meta prohibits the use of the words “rusnia” (“русня”) or “moskal” (“москаль”) [both are derogatory words for Russians], because it qualifies them as hate speech. Given that these features are now ubiquitous, the scale of the blocking is staggering. And here is where a lot of questions arise, because if the content is misqualified, the decision to block an account can be fatal for media or influencers. Although there are mechanisms for appealing blocking, they are not always effective – the complaint is first checked by an automated system. Moderators receive repeated complaints or those submitted by trusted partner organizations. And this makes the appeal procedure very long and complicated for ordinary users.

In addition to the targeted blocking of pages for the distribution of inappropriate content, platforms have another approach, more comprehensive and less targeted – “war on coordinated inauthentic behavior”. In this case, social media do not analyze the publication itself, but the person’s participation in coordinated actions: organized distribution of manipulations, hidden political agitation, etc. For example, during the 2020 US election, Facebook deleted about 11,000 accounts and 12,500 pages. It is important that a feature of most social media is the requirement of authenticity of accounts – you cannot create fake pages (if the profile does not clearly show that it is a fan page or a creative page, it will be deleted). These are such accounts that are most often deleted. However, sometimes restrictions also affect ordinary users who do not consciously participate in coordinated campaigns, but simply repost messages that fall within their sphere of interest (and are part of such a coordinated campaign). Most often such cases occur during election periods, but sometimes they also happen in the context of armed conflicts. And then the consequences of misclassifying the type of behavior have very large-scale consequences, because the topic of war is common to the audience of the entire State, regardless of age or social group. That’s why more and more people are affected by improper blocking.

Sometimes blocking is based on hashtags. In Ukraine, there was a period of #Bucha and #Irpin blocking, when thousands of posts with evidence of war crimes were removed from the platforms. The restriction was imposed due to an alleged violation of the ban on the coverage of violence. However, in practice, this led to the blocking of hundreds of accounts, for which this was not the first such “violation” in the context of the war. This case demonstrates the need for a more careful evaluation of restrictive measures in an information field filled with information about armed conflict.

Crisis protocols. Large social media must quickly adapt to emergency situations – pandemics, natural disasters, civil unrest or international wars. In general, the process of developing such protocols is lengthy and requires the involvement of many stakeholders, but the requirement to create them has already been reflected in the Digital Services Act (a novelty introduced in light of the Russian aggression against Ukraine). However, as a general rule, a few things should be kept in mind:

- Crisis protocols are not an adaptation to the situation “on the ground”! It is an algorithm developed in advance by a platform based on sociological, historical, political and technical research. Of course, after COVID-19, it became easier for social media to respond to some emergencies, because 2020 became a challenge in the context of adapting platforms to numerous restrictions. However, this does not mean that platforms should improvise all the time. The entire social media team must be clearly aware of the sequence of actions in case one crisis protocol or another is triggered. Otherwise, the platform runs the risk of finding itself in a situation where any decision is ineffective (particularly because developments during armed conflicts are much faster and the consequences more fatal than during the pandemic).

- Crisis protocols cannot be the same for different cases. It can’t be a “contingency document.” One algorithm needed to be created for the pandemic, for the armed conflict such an algorithm would be completely different. Moreover, ideally, crisis protocols for international and non-international armed conflicts should differ. If the platform is capable, it is desirable to develop an action plan for each region where an escalation of the conflict can be expected. For example, the situation in Libya escalates from time to time, shelling in Nagorno-Karabakh has recently started again, the unceasing consequences of the genocide in Myanmar – and these are just a small part of the points on the map for which a separate response strategy should be developed. It is worth noting that, among all social media, Meta has a list of “crisis regions”, but neither the procedure for its formation nor the plan of action regarding this list after the crisis escalation is made public by the platform.

- Local experts should be contacted to develop targeted crisis protocols. The option of appearing to be the smartest always looks tempting, but the task of platforms is not to declare a readiness to respond, but to be able to do so when necessary. And this is where we can see the chaos. We have already talked about Meta’s permission to spread calls for violence against Russians in the context of the war in Ukraine and the company’s further backlash – justification and denial of new policies. This is an example of the lack of testing of crisis protocols before the crisis itself, which leads to the platform having difficulty in choosing one solution or another. Should we say that constant policy changes are a negative thing, because they are mostly unpredictable for users?

- Crisis protocols should be reviewed regularly to assess the effectiveness of certain measures for a particular region or type of problem. Thus, in particular, conclusions should be drawn regarding both successful policies and measures and negative experiences. This, in turn, requires constant monitoring of the environment in which social media operate and adaptation of the crisis protocol to specific circumstances. For example, when the conflict transitions from national to international, etc.

Finally, it should be remembered that any procedure for developing a crisis protocol cannot take place without consulting civil society organizations, both international and local ones. Otherwise, the platforms run the risk of creating ineffective mechanisms, content of which will be completely out of step with the realities of life. Are there any good examples of such cooperation? Let’s be honest: no. After the Russian full-scale invasion, Meta started to work in this area, but the efforts are still insufficient. We can only hope that the first steps indicate a serious concern about the issue of responding to crises, rather than a declarative step to preserve one’s reputation.

Escaping regulation. Over-regulation naturally leads to an outflow of users to other resources. This is what once happened with the migration of neo-Nazis from the more regulated Facebook to the open space of 4chan, Reddit, and Tumblr. A similar situation arises during armed conflicts: let’s recall the discussion about self-censorship and the fear of blocking. If users realize that they can lose a page with several thousand subscribers for using the word “rusnia” (“русня”) or “moskal” (“москаль”) – they are unlikely to actively post content that bothers them in such a social media outlet. In contrast, people will migrate to resources with less moderation (if no moderation at all).

Now in Ukraine, this phenomenon is observed with the replacement of classic social media with instant messaging platforms. The most popular, of course, are Telegram and WhatsApp. WhatsApp still tries to prevent the spread of disinformation and illegal content – it limits the number of participants in public groups/channels (maximum 512 users). At the same time, using Telegram is more problematic. Many questions about this instant messaging platform existed even before the full-scale invasion, but after February 24, the number of questionable decisions of the platform skyrocketed. Let’s find out what the problem is.

The story of one paper plane. First, Telegram has its office in the United Arab Emirates and is registered in the British Isles. But according to Bloomberg, the company’s registered address is London. It is officially known that Telegram cooperates with German and Russian authorities (it can transfer user data if there is a court judgment on suspicion of committing a crime). The question of whether Russian authorities will qualify all Ukrainians as terrorists and criminals is, of course, rhetorical. Moreover, back in 2020, a study by Liga.net showed that Telegram’s super-security, which the developers were claiming everywhere, was also a kind of myth.

Telegram was blocked in Russia in 2018, but the blocking was lifted in 2021 without any proper explanation. Some say that the Russian government has simply given up trying to restrict access to this resource, but is that really the answer? Despite many dubious points and significant risks, Telegram is still actively used even in a country at war. And this is facilitated by the State itself. For example, in the first months of the full-scale invasion, the Ukrainian State authorities created dozens of bots and Telegram channels with information about shelling, air raid alerts, evacuation, and other emergency news. This helped keep all communications in one place, because most of the audience used instant messaging platforms – alongside private chats and information channels.

The information channels, though, were the ones that raised the most questions. And this is the second point of the story about the dangers of Telegram in times of armed conflict. From a technical point of view, until last year, the platform had absolutely no profit – for a long time there were no paid services, paid registration, or the option to donate money to the platform. A logical question arises: taking into account the amount of information in the network and the cost of maintaining servers for storing such data – where did the funds come from? Another rhetorical question! However, without resorting to discussions about foreign influence (for now), let’s take a look at how public channels in Telegram function and why they have a significant impact on the Ukrainian audience.

First of all, advertising on private channels is ordered directly from the channel owner. And restrictions on the content of information are very generic: No one will let you distribute calls for violence, hate speech, child porn and a few other categories. Everything else is limited solely by the moral qualities of the channel’s administrator. In other words, you can distribute any content that does not fall under these seven restrictions. And they are by no means strict.

Options for complaining about content on Telegram (spam, violence, pornography, child abuse, copyright infringement, personal data, illegal drugs)

What kind of consequences does this usually lead to? The creation of anonymous political channels that subsequently spread lots of disinformation, backstabbing gossip, scandalous stories and other material that can unleash panic and other violent public reactions. Even without the involvement of politics, channels claiming to be reliable sources of information are popular, but in fact spread fiction, political propaganda, and fakes. A recent study by Detector Media provides an excellent example of a popular Telegram channel: “Trukha⚡️Ukraine,” which often spreads manipulative information in pursuit of breaking news. As a consequence, the Russian media accuse Ukraine of propaganda and biased news. Ukrainians themselves actively disseminate inaccurate and incomplete materials further, which clearly does not help information hygiene in times of war.

- Secondly, Telegram makes it completely impossible to distinguish between pro-Russian content and other information, which is especially dangerous in times of war. Moreover, we are not talking about explicitly Russian-focused channels, but rather those where propaganda of separatism, violation of territorial integrity and sovereignty is spread covertly, “between the lines”. For example, they recognize Russia as a “serious global player” or are they looking for traitors everywhere.

Infographics of Russian propaganda in June – Centre for Strategic Communications and Information Security

According to the aforementioned Detector Media analysis, the number of subscribers to such channels is growing faster than that of objective sources of information. It was on such channels that Opposition Platform – For Life often ordered advertising at the beginning of the year. And, what is most annoying, they are reposted from time to time by reputable resources. As a result, we have a rather sad picture, when the original source of disinformation cannot be found in a complex web of reposts and re-reposts. But the effect is quite significant.

Worst of all, Telegram has no clear rules of use and is not an “open to cooperation” network. Of course, since the start of the full-scale war, there have been several changes to the instant messaging service’s policies: such as translating news from Ukrainian. But neither restrictions on disinformation nor increased control over calls for war have been or are planned. Any attempts at communication are more often than not ignored, both by the public sector and in the expression of initiatives by governments. And at this point it is time to ask the most interesting question, which was the starting point of this study: What if social media are almost uncontrollable? Operating in the United Arab Emirates or in other countries where rights protection mechanisms are the most difficult to implement in practice, platforms actually become a “safe harbor” for the distribution of illegal content. And there are several solutions here – either break through the iron wall and establish cooperation on a horizontal level (without the possibility of sanctions), or look for a mechanism to prevent violations within the State. Let’s look at both options.

Episode II: Interaction Awakens

The issue of social media cooperation with governments has always been a tricky one. Firstly, because the censorship sword of Damocles hangs over the platforms every time they collaborate with one State or another. Secondly, cooperation can come in many forms: co-regulation, ad hoc cooperation, counseling, etc. And depending on the model, there will be different consequences for platforms that do not want to comply with certain government requests: from fines and blocking to the absence of any influence (because of the trivial lack thereof). In addition, the key point is that cooperation is needed not only and not so much by platforms as by governments. Classic media needed State permits to use the spectrum, without which they could not get on the air and have minimal influence – today, everyone distributes information online without any permission. Therefore, in order to maintain minimal control, the State encourages social media to cooperate in every way possible. And here several questions arise:

- Do platforms need to cooperate with everyone? Let’s imagine that tomorrow Meta announces cooperation with North Korea or China, where the index of human rights violations is record high. It is unlikely that the public reaction to such a statement will be favorable. Social media, on the other hand, are always at a crossroads: trying to minimally influence even such States, or not spoiling one’s reputation by cooperating with them. Often States at war use platforms for mobilization, undermining negative attitudes among the population, calls for aggression, etc. And here the main task of the platforms is to try to communicate, and if they fail to do so, to withdraw from the dialogue in time and not make concessions to the manipulators and aggressors. And under no circumstances allow the promotion of war or violence, because the lack of cooperation does not mean the absence of content moderation. For example, in the context of the war in Ukraine, social media tried to cooperate with the Russian government to prevent calls for violence and hostility (2014-2015). But attempts were not successful, and the change of official rhetoric to open propaganda of aggression in 2022 finally put an end to cooperation. The situation was only exacerbated by the adoption of a law banning fakes about the Russian army, which led to the closure of many media outlets within the State and the withdrawal of foreign media from the Russian market. In fact, it signaled that the field for cooperation did not exist, for this would have meant at least partial recognition of aggressive narratives and the opening of a forum for their dissemination. As a consequence, platforms should formally remain neutral and communicate equally with all governments, but this should happen without crossing the red lines. As soon as cooperation is threatened with large-scale violations of human rights, it is worth leaving the dialogue. It is interesting that TikTok is the only social media outlet that was not sanctioned in Russia. Although it suspended its own services after the implementation of the so-called anti-disinformation law, the short period between the adoption of the law and the temporary withdrawal from the Russian market was not marked by any sanctions (as opposed to penalties for other social media).

- Are social media willing to cooperate? Ideological and financial arguments come into play. And while ideologically the platforms always cheer for the end of the armed conflict, they are not always ready to pay half of their annual budget for it. That is why, in some cases, the answer depends on the balance of price and damage. A conditional benchmark would be the following question: Would Meta be willing to leave the US or Indian market (where the company has the most profit) because one of those nations unleashed a war? After all, unwillingness to cooperate often leads to fines and blocking, as Meta’s already mentioned experience in Russia because of its aggression against Ukraine shows. On the other hand, we have the example of Telegram, which does not want to cooperate due to the declaration of increased neutrality. Probably also because of the fear of sanctions and the possibility of losing the audience from the aggressor country.

- Is everyone cooperating voluntarily and in good faith? Cooperation does not mean blindly imposing restrictions dictated by the State. Social media, unlike States, are interested in maintaining a neutral status. This means that in parallel to communicating with the State authorities, they should make efforts to increase digital and media literacy – that is, using policies that will neutralize malicious content without involving the State. At the same time, cooperation should not be declarative. Declaring support without any real action can hardly be considered effective cooperation. Rather, it is an attempt to avoid blocking and sanctions for inaction. It is obvious that such steps are not the high point in measuring good faith, and therefore responsibility for them may come later. This is what happened to Facebook after the failure in Myanmar – an independent fact-finding mission noted its special role in inciting genocide, which significantly affected the reputation of the platform.

- When does cooperation become critical? In crisis communications, there is the concept of “risk window”, which is wide open in the presence of an armed conflict on the territory of the State. And at such times, conscientious governments and platforms should seek contact with each other to have awareness of the context of the problem, to find ways to reduce tensions and prevent further escalation. Again, this is not limited to content restrictions per se – more often it is about the geolocation function, the ability to protect the user privacy, the definition of forms or ways of spreading calls for war or hostility. The State can also act as an intermediary in communication between social media and human rights activists, local media, and digital rights experts. This will allow contextualizing the conflict, but at the same time will not undermine the neutrality of social media.

Since the beginning of the war, the Ministry of Digital Transformation of Ukraine has sent numerous requests to Apple, Google, Meta, Twitter, YouTube, Microsoft, PayPal, Sony, and Oracle to establish cooperation and prevent illegal content. For example, this involved blocking Russian resources that spread calls for war and hostility. NGOs in the field of digital rights protection were also active, preparing a letter to Telegram with recommendations for improving the platform’s work in the conflict-ridden region. As you might have guessed, no response was received from the platform administration.

To conclude the topic of cooperation, this mechanism is not a cure-all solution and depends on the willingness of both parties to make efforts, as well as on the intentions of the parties regarding the cooperation results. While the State perceives such an opportunity as an additional field for propaganda, this is clearly not something that will encourage social media to continue with providing support. Platforms should not make concessions if they are under pressure and constraints. After all, their job is not just to communicate in good faith with all governments, but to protect users’ rights. But what should bona fide States, which are not heard by the platforms themselves, do?

Episode III: The State Strikes Back

Armed conflict is a matter of national security. While social media themselves are unable to overcome calls for war, hate speech, or manipulative information that threatens people’s lives, and there is no space for dialogue, States resort to more radical measures. Moreover, radical does not mean illegitimate. This is rather the last one among possible alternatives – sanctions. It should also be noted that additional restrictions are often applied during martial law and derogation from obligations under international treaties. For example, since February 2022, such a regime has been implemented in Ukraine in relation to the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. This means that the State can impose additional restrictions to protect national security. What measures can be applied to social media?

Fines. One of the reasons behind cases like Sanchez v France (liability of a page owner for comments under his post) is that it is easier for States to punish individuals who are under their jurisdiction than to look for a needle in a haystack and try to hold the platform accountable. However, this approach, fortunately or unfortunately, does not work at all in the context of armed aggression: Most of the messages are broadcast across borders, and there are so many of them that every author can hardly be held accountable. That is why attention should be paid to the resource, which must take appropriate measures to stop violations and prevent them in the future.

On the one hand, the platforms themselves require clear regulations from the State, and also try to regulate policies regarding particularly dangerous content in more detail. On the other hand, social media are not very keen on introducing sanctions for violations. Given the amount of material constantly circulating on each platform, it is impractical and short-sighted to apply harsh sanctions immediately. That is why one of the best options for punishing violations is the imposition of fines.

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has previously pointed out that fines create a “chilling effect” on freedom of expression. However, practice shows that it is now the mildest way of responding to the inaction of social media. For example, the German legislation with fines of up to EUR 50 million for a single violation has only improved the platforms’ performance. This stimulated the development of effective algorithms for detecting violations and responding to them. Currently, most countries are guided by the German example: France, Austria, India already have fairly strict regulation of platforms. The Council of Europe has recently expressed a tougher position.

The key act in this area should be the Digital Services Act of the European Union, which also establishes fines or periodic penalty payments as the main sanction. Unlike previous, rather voluntary standards, this document introduces a clear and understandable system of responsibility, where tech giants risk losing billions of dollars for systematic violations of legal requirements (the fine can be up to 6% of the company’s annual worldwide revenue for the previous year). Such amounts exceed even the sanctions in German law, which were considered extremely severe.

At the same time, we should understand that a system based solely on fines runs the risk of turning them into a “violation fee”. That is, platforms should not perceive fines as a price for non-compliance with freedom of expression standards. Otherwise, such a sanctioning mechanism would be meaningless. And for this purpose, a system should be developed to respond to violations, which would be based primarily on the level of harm from the platform’s activities.

Blocking social media. During an armed conflict, the level of public danger and the possibility of implementing illegal appeals in practice is much higher. While in peacetime it is still possible to tolerate the existence of a resource that does not perfectly perform its function of responding to complaints, in times of war it can be a matter of saving hundreds of lives. That is why the unwillingness of the platform to cooperate, ignoring more lenient sanctions (e.g., fines) is an additional justification for more stringent measures. In particular, blocking specific resources (especially in cases where the State has no jurisdiction over them, and therefore cannot impose other, less restrictive sanctions, and the negative impact on the audience only increases).

Here it is quite interesting to compare the discourse with the blocking of large media. Until recently, a total ban on the circulation of print media or the broadcasting of television channels was considered excessive and almost never met the standards of freedom of expression. However, in 2019, the judgment in Zarubin and Others v Lithuania appeared, where the ECHR emphasized that journalism and the media must be responsible in their behavior, and in NIT S.R.L. v Moldova the ECtHR emphasized that the ban on the media distribution may take place in the case of systematic violations of a serious nature (dissemination of hate speech, child pornography or regular violations of copyright). Of course, these decisions did not apply to the circumstances of an armed conflict, but this approach was later applied in the circumstances of Russian aggression. For example, the European Council banned RT and Sputnik, some of the largest Russian channels and means of war propaganda.. One of the essential arguments was that the European audience believed in pro-Russian propaganda and justified armed aggression. Importantly, Meta, Twitter, and YouTube were the main distribution channels for the banned media. In response to these measures, a representative of Meta made a statement regarding the approval of this measure and the company’s consent to its implementation. YouTube did the same. That is, conceptually, the discourse regarding blocking is gradually taking the side of restrictions in exceptional circumstances (in particular in times of war).

Of course, a ban on one media outlet is somewhat smaller in scale than a ban on a social media outlet with hundreds of media. However, as practice shows, it is the level of danger of the resource and the (in)ability and (un)willingness to prevent violations that are important in the evaluation. The ban on social media used to be considered an overly radical step: The blocking of Russian VKontakte has long been the object of criticism on the part of international human rights organizations. Despite the difficulties with the legal grounds for the blocking, it is now interesting to assess the need for this measure, in view of the real consequences of Russian war propaganda (the social media outlet came under the complete control of Russian State bodies at a certain point). Sociological studies indicate that after the imposition of sanctions on VKontakte, the messages on the platform became more pro-Russian, spreading more and more hate speech and anti-Ukrainian narratives. But the blocking in Ukraine at one time significantly reduced the media’s reach, reducing the impact of such narratives. That is, if the media outlet was still available today, the level of violence would be much higher, and the evacuation of the population from the war-torn regions would be much more difficult. And the main argument in favor of blocking, again, is the control of the resource by Russia and the inability to communicate with the administrators to prevent illegal content.

The situation with independent platforms ready for cooperation is different: they are rarely targeted for blocking, even in times of war. In this context, political and technical aspects are important. We are talking about the ability of the State to control information narratives and effectively regulate the information space (counteracting propaganda and illegal appeals). Thus, so far, Russia, unable to conceal materials indicative of war crimes and also contrary to State policy, has resorted to large-scale blocking of independent social media. It is obvious that this measure has neither legal grounds nor real practical necessity, because it is aimed at censorship. In contrast, the Ukrainian authorities are actively using the possibilities of the platforms – moreover, not so much for State propaganda as for reassuring and calming Ukrainians down, stopping panic, organizing evacuations, etc. This example clearly shows the difference between practices aimed at protecting human rights and preventing the free circulation of data to cover up crimes.

In its recent decisions, the ECHR did not rule that a complete blocking of online resources is completely illegitimate, but has merely indicated that such a measure must meet the three-part test: to be legal, legitimate and necessary in a democratic society. You can read more about the legal requirements for social media blocking measures in this material. The described standards are also applicable during an armed conflict.

Restrictions at the provider level. A separate issue is the activity of providers that provide access to prohibited resources. For example, access to VKontakte was blocked at the level of providers (because blocking at the hosting level was technically impossible – it is unlikely that the management of the social media outlet would agree to block its own services for users with Ukrainian IP addresses). When sanctions were imposed in 2017, Ukrainians were asked to report the providers which did not comply with the requirement to block access to the Russian social media outlet. In 2019, some providers started unblocking banned sites on their own. Given that the blocking of resources for providers was a direct obligation – the failure to comply with such requirements should entail legal responsibility. Therefore, a separate model of responsibility for accessing banned resources exists for intermediaries generally providing access to the Internet. This can be both fines (as the mildest type of sanctions) and more severe measures such as banning the activities of the provider. By the way, an effective and high-quality model of provider liability for providing access to harmful, dangerous resources is laid out in the media draft law.

Removal from Google/App/Microsoft Store. A common practice is to regulate access to content within a particular State. An example is one of the EU Court of Justice’s rulings to block access to search results within the EU. It indicates the technical feasibility of geographically restricted measures, and their recognition as legal under international law. And if the State has already decided to block the social media, then such a measure should be at least effective. For example, after blocking VKontakte, the platform began spreading information about the possibility of bypassing the restriction on the territory of Ukraine through proxy servers. This means that there will be no need to use workarounds like VPN anymore, you just need to download the Vk.com app from the App/Google Store. That’s why it was necessary to make the app download unavailable from the territory of Ukraine.

Measures may concern both the removal of the aggressor country’s apps from online repositories around the world and the blocking of specific apps on the territory of the aggressor country. In general, the practice is not new for Apple and Google themselves:

- In 2019, Apple made 634 apps from the online store unavailable on the territory of the requesting States due to their non-compliance with the national laws. Overall, Apple notes that it complies with the government requests to remove apps 96% of the time.

- The situation is similar with the Google Store, from where apps are removed locally or globally, depending on the severity of violation.

- Applications can also be made unavailable on the territory of the aggressor country. About 7 thousand applications are blocked for download in Russia due to its aggression against Ukraine at the request of developers.

- Google and App Store remove apps involved in the financing or promoting of terrorism, violence, discrimination, or spreading other types of illegal content.

- After all, after blocking Russian RT and Sputnik, Google, Apple and Microsoft Store removed the apps of these channels from the repositories, and Amazon disabled the function of creating new accounts from Russia and Belarus (the companies also eliminated the possibility of re-registering deleted apps).

Removing applications from the repositories during the war is quite an effective means, because blocking by itself cannot fully prevent access to the resource. At the same time, deplatforming significantly narrows the field for the distribution of illegal content, and what’s more, it can be geographically limited. Therefore, this sanction is the best: On the one hand, it is the least restrictive measure for freedom of expression. On the other hand, it prevents harmful content from spreading on the territory of the State during a vulnerable period. But, as is the case with the usual blocking, this restriction is still one of the toughest sanctions. That is, it should be applied when the platform is unable or unwilling to regulate the exchange of information on its own, is not ready for cooperation, and fines cannot be imposed either due to lack of jurisdiction or the failure of the social media outlet to comply with court orders. In fact, such a measure, like blocking, is the last step that States should resort to in order to protect national security in the context of an armed conflict.

Internet blocking. Restrictions applied by the most “democratic” countries. Relatively recent examples: Russia has been trying to cut itself off from the world wide web, while China has had the Great Firewall in place for quite some time. And in no situation was this measure considered an adequate response to any type of violation. Thus, the international organization AccessNow even compiled a list of “States for public condemnation” that constantly resort to such measures. And here the difference in measures applied by Ukraine is indicative: Attempts to ensure the availability of the Internet on the territory of the entire State, even in the regions under occupation, and the policy of Russia – which tries to create an internal Internet so that citizens do not get access to the truthful and objective information.

Therefore, when choosing a response measure, proportionality and available alternatives should be carefully weighed. For example, if a social media outlet is cooperative but is slow to respond to complaints for certain reasons, this is clearly not a reason for blocking. At the same time, the complete lack of adaptation to the context of war and the de facto permission to spread dangerous narratives, as well as disregard for punitive sanctions, can serve as grounds for tougher sanctions.

Episode ІV: A New Hope

Regulating the information space at a time of armed aggression is certainly not an easy task. Let’s be honest, this task is quite difficult even in peacetime, given the number of discussions surrounding the aforementioned Digital Services Act. However, the war should not become the basis for uncontrolled restrictions on social media and instant messaging services, because sometimes they remain the only resources from where readers can get objective and vital information. In the same way, one should not expect ideal behavior of platforms, because it is hardly possible to foresee absolutely everything and respond in time to each of the threats. The question is about the quality of the efforts made to protect a secure information space.

At the same time, it should be remembered that responsibility in such a tumultuous period cannot be placed solely on platforms, the State or the public sector. Protecting human rights and reducing harm from illegal content is everyone’s job. While the basic responsibilities of all stakeholders are already outlined in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, below you will find brief guidelines that further outline the tasks of each of the abovementioned actors in times of armed conflict.

States have to:

- Be open to communication with platforms and other stakeholders.

- Communicate new human rights restrictions introduced during armed conflict in a timely and clear manner and communicate any changes to policies.

- Avoid using platforms as a source of propaganda, encouraging the dissemination of unbiased information about the armed conflict.

- Engage with platforms to preserve evidence of war crimes and to transmit such information to the competent authorities (without requiring the deletion of such information after transmission to the State).

- Engage with civil society when imposing human rights harm reduction restrictions, as well as with platforms to verify the technical ability to implement restrictions.

- Review restrictions for their relevance and remove restrictions that no longer meet public needs (in particular, are not necessary to protect national security or are not effective in achieving such goals).

- Promote media literacy and critical thinking, report the possible spread of misinformation, and the need to check critical news.

Platforms have to:

- Shift the focus of their policies and practices toward respect for human rights (in particular be willing to sacrifice business interests), enhanced protection of vulnerable groups (activists, journalists, national and ethnic minorities, people in the occupied territories, conflict victims, etc.).

- Conduct regular monitoring of the situation in high-risk regions and determine the level of threat.

- Develop and regularly update crisis protocols, which should, if possible, be tailored to the context of a specific “dormant” conflict or situation where escalation is possible.

- Cooperate with States, the public sector, and independent experts.

- Ensure protection of evidence of war crimes (e.g. photos of destruction of civilian facilities, videos of shelling or even torture, texts with eyewitness testimonies, etc.) by organizing a system of conditional access to such information (warnings and additional actions to see such data).

- Ensure additional privacy protection for vulnerable groups.

- Develop users’ media literacy, flag unreliable or suspicious sources of information, warn about the possible spread of disinformation, emphasize that verified accounts do not necessarily spread truthful data.

- Respond quickly and effectively to changing circumstances and communicate constantly with local experts to identify potential risks and develop countermeasures.

Civil society has to:

- Create a platform for stakeholder collaboration and act as an independent facilitator for crisis communication, filtering out bias when necessary.

- Proactively signal problems in the regulation of the information circulation in social media, update in their policies (including crisis protocols), and changes in State regulation, and analyze whether such changes comply with human rights standards.

- Verify that public and private policies comply with social realities and encourage the adaptation of restrictions to public needs, and promote the update of regulation.

And we, as instant messaging services and social media users, should be careful about the information consumed. We should also remember that any complaint helps platforms to improve their work. So do not be lazy or discouraged – everyone has an influence on moderation policies, so lets use it wisely!